|

In the

first two articles in this series (see MOTHER NOS. 71 and 72),

I dealt with ways to secure shelter and water . . . the two

most important requirements for anyone facing a survival

situation. On the other hand, one seldom needs a fire

in order to stay alive. But because a good blaze can be used

to cook food, sterilize water, create tools, and—of

course—keep a survivalist warm and comfortable, I've placed

firemaking third on my list of valuable wilderness skills.

It's important to know how to ignite a

fire without the aid of a cigarette

lighter—which is simply a modern form of the old

flint-and-steel system—or matches. After all, you might

unexpectedly find yourself thrust into a situation when you

have no supply of purchased flame starters. Or if you're

camping and your matches get wet or lost, you might be forced

to end your trek early if you're unable to get a blaze going

without artificial aids. What's more, no self-respecting

outdoors purist would want to be dependent on a finite

supply of matches.

In my school I teach 17 ways of building

fires. In my opinion, however, the best overall flame

starter—and the one I'll share in this article—is the bow

drill. Learning how to work with this tool will give you a lot

of satisfaction, and add to the security you'll feel when

traveling through the woods.

Before I go into the details of making a

fire, though, let me emphasize that whenever you practice

this—or any other—outdoor skill, it's important to do the best

job on the task that you can possibly do. Consistently careful

craftsmanship—even in rehearsals—will not only insure good

results but also improve your ability to get the job done

under adverse conditions. Most native Americans aimed at this

same perfection of skill on an everyday basis. They felt that

anything—including, but not limited to, living plants and

animals—that they took from the Earth Mother was a gift from

the Great Spirit. Of course, doing a shoddy job of employing

the gifts would, in effect, be showing disrespect for the

Spirit's generosity, so they tried to make works of art of all

things. Such actions were an integral part of these people's

religious beliefs, and served the purpose of greatly

increasing their survival abilities.

|

|

|

To make tinder, work some light dry wood (such as

this cedar bark) with your hands... until the fibers

loosen (you can soften any particularly stubborn fibers

by pounding them between two rocks)... and you have a

light, fluffy bundle... The fireboard, drill and

handhold... The bowstring is wound once around the

drill... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

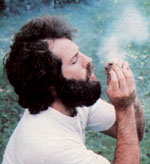

Perfect fire-starting form... Blowing the

tinder-wrapped coals into flame... and thrusting the

lighted bundle into a prelaid

fire. |

PREPARING THE SITE

Of course, before you can make a

fire, you have to choose a spot for it. Your site should be

free of any combustible brush, dried grasses, or leaves . . .

away from low overhead branches . . . and not in an open, breezy area or on an exposed

ridge. I also recommend (as I pointed out in my first article)

setting your fire some six to ten feet—depending upon wind and

weather conditions—away from your shelter entrance.

Once you've picked a site, dig out your

fire pit. This dish-shaped hole should be about a foot deep

and have gently sloping sides. The depression will cradle the

fire, with its coals grouped toward the center, and thereby

help your embers burn much longer than they would in a flat

fire bed. Be sure, though, not to make the hole so deep that

the pit will prevent your fire's heat from reaching you. And

if you're digging in rich, loamy earth or soil that's full of

root stems, line the bed with rocks to avoid the possibility

of starting an underground fire. (Such blazes can actually pop up aboveground miles away, and

months later!) Furthermore, use only stones gathered from a

high, dry area for this—or any—fireplace job, since

waterlogged rocks may explode when heated.

To increase the amount of useful warmth

provided by the blaze, build a simple horseshoe-shaped

reflector around the side opposite your position. Rocks, damp

wood, or even earth can be used to make the semicircular

heat-funneling structure. An experienced survivalist always

builds fires with reflectors and tries to sit with his or her back against a

tree, rock, or shelter. That way, the reflector can help warm

the person's front and (by bouncing heat off the rear barrier)

back as well. And with such a setup a small fire—which won't

use up a lot of wood—can provide sufficient comfort.

An amateur, on the other hand, will often build a

roaring blaze but leave it totally unbordered, and will

therefore have to spend the night spinning at various speeds

to keep one side of his or her body from freezing and the

other from burning! Indeed, the amount of turning around a

person has to do to stay warm when sitting by a fire will tell

you right away whether that individual has good woodcraft

skills. (I call this "the spin indicator test".)

FINDING

WOOD

Most people who attempt to start an

outdoor fire are stopped in their tracks by one difficulty:

locating dry wood. The cardinal rule to remember in this situation is that

any wood found on the ground will have soaked up moisture and

will be quite hard to light, so never collect ground wood for

fire-starting fuel. Instead, gather dead limbs from standing

trees. This wood will always ignite easily. (In fact, even in

the Olympic rain forest—which gets 88 inches of rain a

year—it's possible to pull a dead branch off a Douglas fir,

whittle away only 1/8" of its outer surface, and find dry

fuel.)

Also, try to collect your standing wood

from trees in open sunny areas rather than those near stream

bottoms or lowland regions where fog and moist air likely

collect. You can easily determine whether the wood you're

gathering is dead and dry by breaking off a piece: If the

stick snaps cleanly and audibly, you've got good firewood. In

most weather conditions, you can also find reasonably dry wood

by touch. When your hands are too cold to be sensitive, you

can press the fuel against your lower lip or cheek to feel for

dampness.

You'll need four types, or grades, of

fuel. The first is tinder . . . the light, airy, and

fast-burning material that's used to catch a spark. The dried

inner bark of elm, cottonwood, willow, sage, cedar, aspen,

walnut, or cherry trees makes excellent tinder. Dry vegetation

such as reeds and grasses, dogbane, velvet leaf, yucca,

primrose, fireweed, bulrush, milkweed, cattail, and thistle

(especially, in the last three instances, the plant's

down) will work well, too. In fact, with a

little bit of effort, you can use just about any dried fibrous

plant.

To prepare your tinder, remove all hard,

crumbly bark or inner pith from the gathered fuel and rub the

remaining fibers back and forth in your hands until you've

created a fluffy bundle made up of filaments as small as

thread. You can soften any particularly stubborn fibers by

pounding them between two rocks.

The next type of fuel you'll need is

kindling . . . tiny twigs or slivers that range

from the thickness of a pencil lead to that of a pencil

itself. You can either break kindling material off sheltered,

dry branches or carve the fuel from larger pieces of wood.

Always be sure to keep both this and your tinder absolutely

dry.

Squaw wood, the

next biggest fuel, gets its name from the fact that native

American women collected this pencil- to wrist-width wood as

part of their daily routine. Rather than waste time and energy

cutting huge trees for firewood, Indians burned the small and

easy-to-gather sticks as often as possible.

Last comes large

firewood .

. . too-big-to-break fuel that's added to a fire

only after the blaze is going strong, when you can use damp

wood. (Dry wood, of course, will burn more easily and give off

less smoke and steam.) But don't waste your energy trying to

cut up these sections. Instead, shove the butt end of a large

log into your fire . . . and then feed the rest of the piece

in as it burns down.

And remember: Don't try to take shortcuts

when gathering any of the four types of fuel. Take the time to

obtain the best materials, and your fire will be easy to start

and to keep burning no matter what the weather conditions. In

addition, be sure you gather enough firewood to last

through the night. There are few worse wilderness tasks than

having to leave a snug shelter and stumble around in the dark

to replace your supply.

ADDITIONAL FUEL TIPS

If you want to generate a

tremendous amount of heat, adequate light, and a slow-burning

fire that results in fine cooking coals . . . use hardwood for

your fuel. On the other hand, should you need quick heat and a

lot of light, it's best to find a softer wood such as cedar,

tamarack, or juniper. Wet wood, green leaves, or pine

boughs can be added to a fire to make a thick plume of smoke

and steam that will help searchers pinpoint your location.

Damp fuel can also be used to help you

keep a bed of coals burning overnight. (Green wood

works well for this purpose, too, but don't cut living trees

for fuel unless you're faced with a true survival situation.)

Add a liberal supply to a strong blaze just before you go to

sleep. The slow-burning wood will keep the fire going for

several hours, and produce coals that'll usually last through

the night.

THE TIPI FIRE

Once you've prepared your site and

gathered the necessary materials, it's time to lay the fire. I

strongly recommend tipi-shape stacking for this job. Since the

design allows the fuel to stand high and lean toward the

center of the structure—that is, where

the flames naturally rise—it starts easily, burns efficiently, and throws out quantities of heat and

light. Furthermore, the slanting walls and resulting high

flames help the blaze hold up even in rain or snow storms.

Start with a bed of tinder and then,

working from your finest-grade materials on up, build a

cone-shaped structure. (You may want to lay down a tripod of

firm sticks first, to give the design its form.) Also, be sure

to leave an opening through which you can reach the interior

of the pile to light the fire. This entrance should face the

wind so that the prevailing breeze can help drive the flames

up through your fuel.

I generally put about six inches of

tinder and kindling in the center and add a good supply of

squaw wood—working carefully from the skinniest sticks to

thicker ones—until the tipi is 8" to 10" across and a foot or

more in height. When it's raining, I'll lay small slabs of

bark around the cone to help keep the interior dry until I'm

ready to start the fire.

If you're carrying matches, you can

simply thrust one into the "doorway" of the tipi and watch

your blaze take off (even in wet weather). However, if you

don't have

matches, you'll need an effective alternate method . . . such

as the bow drill.

BUILDING THE BOW DRILL

There are five parts to a bow-drill

apparatus: the bow, the

handhold, the

fireboard, the

drill, and

some tinder. The

bow can

be made by cutting a 2-1/2to 3-foot length of 3/4" green

sapling . . . preferably one with a slight bend to it. Fasten

some cordage made from a shoelace, a strip cut from your belt,

or a tightly braided piece of clothing to the stick's ends

(1/8" nylon cord is a good choice when you're practicing,

since it'll last through many trial runs).

The handhold—the object that

fits in your palm and holds the drill in place—can be made

from a small section of branch, a rock with a depression in

it, or a piece of bone. Almost any type of wood will do, but

it's best to use one that's harder than the drill and

fireboard material.

The next two pieces, the fireboard and

drill (or

spindle), should both be contrived from the same type of wood . .

. and your choice here is critical. You must select a branch

of dead wood that's very dry, yet not rotted. It should also

be a wood of medium hardness: You don't want to use a very hard species

(like oak, hickory, and walnut) or a very soft resinous type

(like pine, fir, and spruce). Cottonwood, willow, aspen,

tamarack, cedar, sassafras, sycamore, and poplar are best.

After you've chosen your wood, cut off a

branch for the spindle (it should be about 3/4" in diameter

and 8" long). Then use a sharp rock or a knife to smooth out

the drill until it is as straight and round as you can make

it, and carve points on both ends

of the stick.

To construct the fireboard, find a branch

that's about 1" thick and 10" long, and whittle it flat on

both sides. You want to end up with a board that's twice as

wide as your drill and about 1/2" in thickness.

The last item needed to make fire with a

bow drill is tinder, which

I described earlier.

BURN AND NOTCH

With all your equipment assembled,

it's time to finish preparing it by burning holes in the

handhold and fireboard and then cutting a notch in the board.

To mark the holes' positions, place a small nick—which will

serve as a starting point—in the center of the handhold and

one in the fireboard. The latter cut should be far enough in

toward the middle of the board to leave room for the

depression that will be burned in by the drill

and for

the added notch.

Now, wrap the string once around the

drill to secure the stick. Adjust the tension of the cord so

that you can't slide the spindle back and forth along it.

Next, set up the components as shown in the accompanying photo

of a bow-wielder.

Take careful note of the form used by

this individual: If you duplicate it exactly, you should be able to start a fire under almost any weather

conditions. The right-handed survivalist (a left-handed person

would reverse these instructions) has placed his left foot

across the fireboard, while he rests his right knee on the

ground. His chest is set firmly on his left knee, and his left

hand—braced tightly against his shin—grasps the handhold and

keeps the spindle perpendicular to the fireboard. The bow is

held in his right hand and moved in line with his body. From

this position the firemaker can easily spin the drill and press

down on it from above. In addition, his body over shadows the apparatus and thus creates a meager,

but valuable, weather break.

When you've positioned yourself and your

equipment properly, begin vigorously moving the bow back and

forth . . . at the same time gradually increasing your

downward pressure on the

handhold. This action will probably feel quite awkward at

first . . . but after you've gotten the hang of it, you'll

soon have drill, fireboard, and handhold smoking and be able

to burn good-sized depressions in both the board and the hold.

Next, it's time to add the most essential

part of the entire bow-drill setup . . . the

notch. This pie-shaped opening should be carved completely

through the fireboard, with its point just short of center in

the plank's burned-out pit. Make your notch a clean,

well-manicured cut.

Finally, you should grease the top of

your drill and the

handhold's socket to prevent friction-caused heat from making

that depression any larger, and to help the drill rotate

smoothly. You can use natural body oils by simply rubbing the

end of the drill stem along the sides of your nose or in your

hair. Pine pitch, animal fat, and slime molds will also do . .

. but don't use water, or the drill will swell and bind up.

And be sure not to mix up the ends of the drill. Otherwise,

you'll get grease in the fireboard, ruin the friction there,

and be unable to make a coal.

MAKING YOUR FIRE

At last, you're ready to start a

fire. Check to see if the ground you're working on is damp. If it's moist, use a plate

of dry bark to give yourself a decent work surface. Next, lay

down your tinder and position the fireboard directly over it,

so that the notch opens to the exact center of the fiber

bundle.

Now, set up the rest of the apparatus

. . . be sure your form is good, your handhold firmly

braced, and your drill straight up and down. Then move the bow

back and forth quickly while slowly pushing the drill

downward. Press firmly until the lower part of the spindle and

the fireboard are smoking violently. But don't apply too much

pressure, or the drill will slow . . . the string will start

to slip . . . and the smoke will quickly diminish.

Once the board has begun to smolder, keep

stroking the bow for ten more complete repetitions. Then

carefully dismantle the

upper apparatus without jarring the fireboard. Next, carefully

slip your knife blade down through the top of the notch to

dislodge the burning dust formed by the abrasive action of the

drill upon the board. Remove the board, and wrap the tinder up

around the glowing ember . . . taking care not to crush the

coal. Gently blow the bundle into flames—turning the tinder,

as necessary, to keep the ember in contact with fresh fuel—and

thrust the burning mass through the doorway into the center of

your firewood tipi.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Very

dry tinder can flame

up dramatically . . . use appropriate caution.]

PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT

All the cutting, burning, greasing,

and stroking involved in using a bow drill may seem

troublesome, but with practice a survivalist can proceed from

start to finish—including making the

entire apparatus—in just under 15 minutes. The task doesn't

require a lot of strength, either . . . form and coordination

are much more important. Indeed, I've often taught

six-year-old children how to make fires by this method.

Learning to use a bow drill may not come

easy at first, but keep at it and you'll soon master an

important survival skill. Then you'll always have the security

of knowing that you can make

a fire, if necessary, at almost any time and in almost any

place.

For more material by and about Tom Brown Jr. and the Tracker School

visit the Tracker Trail

website.

|