|

|

Home →

Survival →

Fire →

Fire Pistons

Some Thoughts on Fire Pistons

Rob Bicevskis

January 2004 |

|

|

|

I have played with fire pistons for a little while. I like units that are made from “plastic” since one can see what is going on. An “all natural” fire piston is great, but it seems more like a magic trick because you can’t see the secret through the opaque wood. With a “plastic” fire piston, one can actually see that “there is no secret!” I’m going to assume that the reader already knows the background of fire pistons.

In my last round of experimentation, I decided to investigate the following things:

- The typical hole in the end of the plunger often does not hold the tinder very well. When the tinder does light, it is difficult to remove the tinder from the plunger.

- With an O-ring gasket the seal is so good that the fire piston can not be carried in a “closed position.”

- How to make a “gasket-less” plunger.

- Experimentation with different fire piston dimensions.

This first picture shows the two basic fire pistons that I made: |

|

|

|

Picture 1:

Polycarbonate Test Fire Pistons |

|

|

|

|

Both units were made of Polycarbonate. I use this material since it is

literally “bulletproof.” I have used plexiglass or acrylic in the past.

Unfortunately, with this material, unless one is extremely careful about

removing all scratches and/or annealing the final product, the fire

piston won’t last too long. Below are pictures of plexiglass fire

pistons: |

|

|

|

|

Picture 2:

Acrylic Fire Piston with Cracks |

|

|

|

|

Picture 3:

Acrylic Fire Piston – Catastrophic Failure |

|

|

|

The two polycarbonate fire pistons in Picture 1 had the following

dimensions:

- Smaller Unit: Bore: ¼” diameter, depth: 2.7”, total length closed:

3.5”

- Larger Unit: Bore: 3/8” diameter, depth: 3.2”, total length closed:

4”

Here is another view of the smaller unit: |

|

|

|

Picture 4:

Mini Fire Piston |

|

|

|

The first problem that was explored was the hole for the tinder.

If the hole is too small, it is very difficult to load and unload the tinder.

If the hole is too big, then a lot of compression is lost and the fire piston is

much less effective.

My solution was to “turn the hole around.” Therefore, instead of drilling a hole

into the end of the piston, I drilled a hole in the side.Bellow is a picture

with this configuration: |

|

|

|

Picture 5:

Variation on Tinder Hole |

|

|

|

Some of the advantages are as follows:

- The shape of the hole naturally holds the tinder in place.

- There is more surface area of the tinder exposed.

- It is easier to see when the tinder lights.

- To remove the glowing tinder is easy – it just slides out sideways with

a fingernail, twig, or knife end.

This solved point #1 on my original list.

Picture 1 shows a normally impossible configuration for an O-ring

fire-piston. O-rings form almost perfect seals – so it is almost impossible to

“close” this type of unit. I really wanted to be able to achieve this

configuration to enable carrying the fire piston. Picture 6 shows the solution

to the problem. A very thin piece of thread, hair, wire, etc. is placed under

the O-ring. This creates a small leak in the system. When rapidly depressing the

plunger, the leak is insignificant. When the plunger is slowly closed, say over

15 seconds, pressure slowly bleeds off and the fire piston stays closed. This

solved point #2 on the list. |

|

|

|

Picture 6:

Leaky O-Ring |

|

|

|

|

The third area of study was to experiment with making a “gasket-less” fire

piston. There are posts on the internet indicating that some people have made

this type of fire piston. There is not data on how this was achieved, so I

decided to do a bit of playing. I considered two options:

- To make the equivalent of a “ground glass” fitting. Glass to glass

fittings can be made by “roughing” up both surfaces. This is often done in

chemistry lab ware. This might be an option for a fire piston – but it would

require very precision machining.

- Using a very slippery, slightly soft material for the plunger.

Solution #1 will have to wait for another day.

Instead, I tried solution #2. The material that I used was UHMWPE. (Ultra

High Molecular Weight Poly Ethylene.) This material is good enough for joint

replacements, so I figured it must be good enough for fine pistons! I turned the

plunger on a lathe, and left a larger diameter at one end. Picture 7 shows the

UHMWPE plunger on the right. For reference, I showed other plungers that I

tried.

In Picture 7 below...

From left to right are:

- Cross-Bore Tinder hole with O-ring gasket

- Cross-Bore Tinder hole with string gasket

- End-Bore Tinder hole with O-ring gasket

- End Bore tinder hole with “no” gasket

|

|

Picture 7:

Various Plungers

|

|

|

|

|

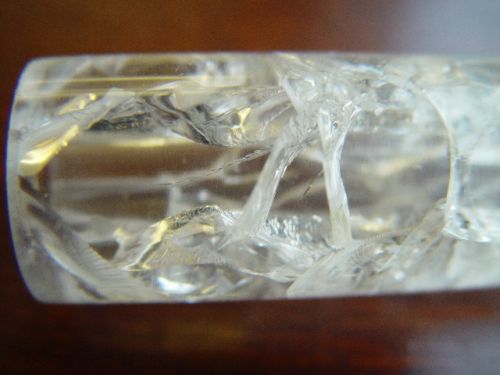

Picture 8 shows the sealing effect of the UHMWPE: |

|

|

|

Picture 8:

Seal formed by UHMWPE Plunger |

|

|

|

|

The UHMWPE worked reasonable well. I could get a coal fairly reliably. It does

have much more friction than the O-ring solution – so is much less effective. In

the end, if one is going to use modern materials such as plastic, or

polycarbonate, then I would recommend going with an O-ring. It is a much simpler

solution and works much better. That took care of experimentation point #3.

The last item related to the effectiveness of various sizes of fire piston.

From physics we know that:

Pressure = Weight/Area

From this we can predict that we can get the highest pressure with the

smallest area. In this case, “area” refers to the diameter of the plunger. This

means that the smaller the diameter of the plunger, the better. In the two units

that I made for these experiments, the ratio of areas is 2.25. What this

translates into, is that it’s going to be 2.25 times easier to get a coal with

the smaller fire piston. There are many people who believe that the bigger fire

piston is the better one. In one sense this is true, in that the “volume” of air

available to be compressed can be larger in a big fire piston, but in terms of

effectiveness, the small bore piston is much better. There are also smaller

frictional losses in the smaller unit. This theory is backed up with results

using the two sizes of unit. The small unit produced coals with almost “no”

effort. The larger unit takes much more of a hit to get a coal. Note that the

larger unit has a lot more air being compressed, but the smaller unit works much

better.

Conclusions

The original objectives were met. Some new ideas came from lots of

experimentation.

- A big improvement on the method used to hold tinder was achieved – the

horizontal tinder hole

- The “carrying” problem was solved by creating a “leaky” O-ring.

- A gasket-less fire piston was built and it worked.

- Different sizes of fire pistons were made to get a feel for how much

better a small bore fire piston is compared to a large bore fire piston.

|

|

|

|

|