|

|

|

|

Home →

Survival →

Fire →

Flint and Steel

Knife & Stone Fire Starting

by Allan "Bow" Beauchamp |

|

|

|

Fire starting in the northern bush can be a real task, especially with the

weather extremes that challenge us so often. I enjoy being out in the

bush on cold winter nights. I often travel on snowshoes, and just wander

all night long. There are many ways to start a fire without the

assistance of matches. I have been working on many of these different

fire starting techniques for many years, and have seen advantages and

disadvantages for each technique.

Each fire starting method also has many variations. These variations

could offer the bush traveler something that could be used in any area.

One method alone will not do everything in every situation

everywhere, and like I always say in my articles, we always need to have

"options." Personally, I prefer to rely on skills that are the most

practical and functional.

Since I spend a lot of time in the bush, I am not much of a "fair

weather fella." If I talk about sleeping in -45°F in the snow and

starting a fire in a primitive manner, I mean just that. By doing this,

I have found that it helps my "options" list. Some things you may read

about that are suppose to work in these elements can fall very short on

performance. This means that I am constantly trying new techniques, and

am always working on the old ones to help me find more and better

"options."

I had found that the knife and stone to be the one way of starting a

fire that I revert to more often than most of the others. It is very

simple, requires minimal gear, which I most often have with me anyway,

and works well in most environments that I have found myself venturing

out into.

When I speak of knife and stone fire starting, I mean just that. I

always have my knife with me in the bush, and finding stones in upper

Canada is not a big deal.

When I selected my knife, I tried to find characteristics that would

work for me. Selecting a good knife will make all the difference in the

world with your fire starting capabilities. I selected a knife that had

a high carbon count (older knifes seem to have more of these blades than

the newer style of blades do).

Most stones that I find in my area are not actual "flint." They fall

into the category of "chert," and in this area, you are most likely to

spot white quartz. If you read my article on Two Stone Fire Starting in

Volume 6, Issue 2 in wilderness Way magazine, you will remember that the

hand strikers were also made of flint. The stones that I have found

around here are harder than steel, which is why my knife and stone

method works well for me.

As I mentioned earlier, each area requires its own unique skills and

materials, so it is up to the individual to explore the best tools and

methods for them. |

|

|

|

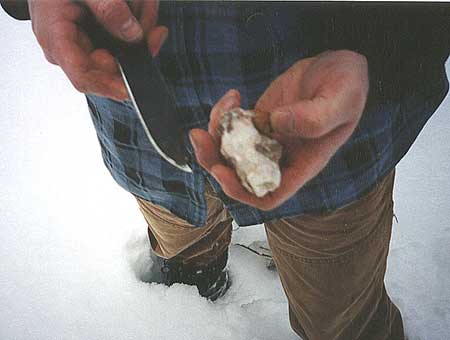

Photo 1

|

In Photo 1, all of the components needed to use the knife and

stone method are shown: a knife, white quartz stone straight from the

ground, and tree fungus. Each piece has its own purpose. The stone is

harder than steel, so that when it impacts with the knife, the knife's

softer blade sends off a spark. By impacting the two components, the

small spark is caught in the fungus, which will hold the heat very well,

and allows it to develop into coal. Simple enough!

|

|

|

|

|

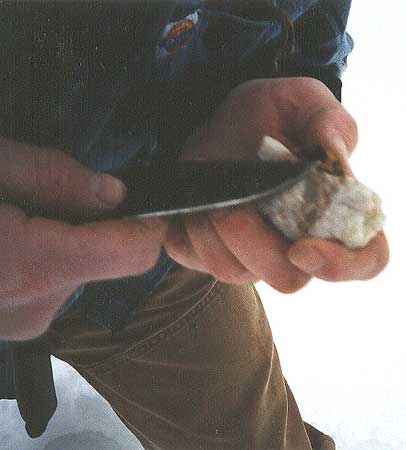

Photo 2

|

Photo 2 shows the pieces in my hand in position before the actual

striking of the spark. The quartz stone rests in my palm. I try to find

a comfortable position for the rock so it sits easily. |

|

|

|

|

Smaller pieces of rock are break-aways from bigger pieces; hence, they

have at least one sharp comer. If you do not have a small sharp comer,

your sparks will not be as good as they could be for sparking. Why? It

is because the sharp comer of the rock impacts with the knife sending a

small shaving of spark off. I have, from time to time, used rounded

stones that I have found on lakeshores. By striking them with the tip of

my knife, I have gotten sparks, but they are not as strong.

Using a sharp edge is the best. How do you know it is sharp? Run the

stone's edge along your forearm slowly; and if it feels like it would

cut you if you put to much pressure on it, you have a good sharp edge.

So, hold the small stone in your hand, and find an edge that is

sharp. This edge must be positioned where the knife-edge will intersect

with the rock. The back edge of the knife will be impacted against the

stone's sharp edge, and cause shavings of metal from the back of the

knife blade to fly off into a spark. Hold the stone in one hand loosely;

then grab the knife along its spine with the sharp edge facing your

hand.

When you cradle the quartz stone (or flint) in your hand, try to get

the sharp edge on the "horizontal plane." Then, move the angle of the

sharp edge of the stone less than ninety degrees, so that it seems that

the stone's edge will shave a piece of knife off.

This technique does have some disadvantages, but I feel for the

advantages the practical gains learned far outweigh the latter of the

two. The disadvantage is that the knife blade has the sharp side facing

towards your inner hand. This could cause a nasty cut should your grip

slip, because of cold or wetness. If this poses a real concern for you,

try using a Nicholson brand me. It will allow the same availability of

sparking, but in a safer manner. However, you have to remember, to carry

the me with you in the bush! Practical?

Now, you are ready to add the other component. Taking your knife

or the file) in your hand, use the thumb of your hand. Place it on one

side of the spine and your two first fingers on the backside. The knife

should be held in such a manner to display the back edge of the knife

facing away from you, and the sharp edge facing towards your inner hand.

Ensure the knife's sharp edge is away from the palm of your hand. Slide

the knife so that your fingers grip it about mid way along the blade. I

have found that this works very well for me.

The stone's edge should be in the palm of one hand, with the edge

less than ninety degrees, and the knife held vertically in the other

hand. Practice this method gently at first, getting a feel for the knife

and sparks. Try a vertical stroke from the knife's back edge, impacting

and creating a spark as it glances against the sharp edge of the stone,

doing a slow follow through each time.

Using a vertical motion, we want to just glance the blade's back

against the sharp edge. Not much impact is needed here, so do not try to

hit them together too hard; just let it flow. You will see that one time

you will get sparks and the next time you will not. Stay with it. Try

learning something from each try until you feel comfortable.

Practice this for a while until you have it fine tuned. You will know

you are ready for the next step when you can hold it comfortable and use

good follow through strokes that will make a spark each time. Soon you

will feel that you are ready for the next step -- the sparking stage. |

|

|

|

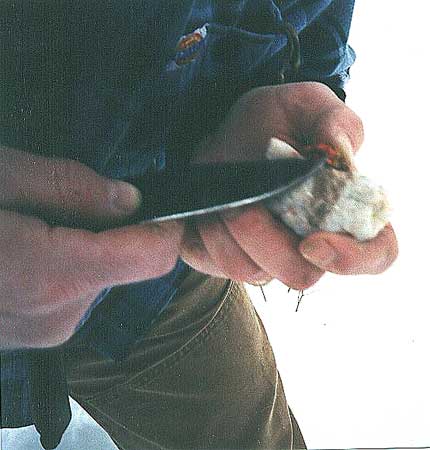

Photo 3

|

I am using my tinder fungus piece. Photo 3. This particular piece

is from the birch family This fungus is found in the area that I am in,

and I use it as much as I can. I am holding the desired position for

the fungus and the stone as a combination. I cradle the stone in my palm

loosely, then after selecting my fungus tinder, position it under my

thumb as seen in the photograph.

|

|

|

|

|

This can seem very tricky the first time juggling the tinder, and

holding the stone. If you find it hard, try using a bigger piece of

tinder. What you are looking to accomplished is that the piece of

tinder must catch the spark for this technique to work. If it is over

the edge of the stone too much, the knife's backside, when hitting the

sharp edge of the stone, will simply break it off. If the tinder is back

away from the stone's sharp edge too far, it will not catch any spark,

no matter how good of a technique you have.

Hold the stone in your palm, and stand the knife's edge against the

stone's sharp edge. Look at it. You should see the stone's sharp edge at

less than ninety degrees to the knife's vertical position. Then, slide

the tinder under your thumb until it just touches the knife's back side,

and hold everything in place. With a glancing blow from the knife, try

to lightly create the spark that you practiced earlier.

With every glance, I always check to see if a spark has caught in the

tinder. There have been many times that I have thought that I had not

gotten any sparks, only to see them break off with the next glancing

blow from my knife and end up on the ground. Remember: Just because you

do not see it, do not think that it is not there.

|

|

|

|

Photo 4

|

In Photo 4, you can see these three combinations held in the

right position to work together: the vertical position of the knife; the

tinder as dose to the knife's edge as we can get it; and the less than

ninety degrees of the stone (on the horizontal plane). Notice again how

I have my fingers positioned away from the blade's sharp edge.

|

|

|

|

|

Photo 5

|

Photo 5 shows the tip of the knife, and that the tinder has indeed

caught the spark. This is easily seen against its brown soft exterior,

and this particular tinder has a distinct smell. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 6

|

You can see at this point the sparking process. Photo 6. The spark

is trying to develop into coal for fire starting. Gently blowing on the

coal, and with some patience, it will spread quite easily. At this

stage of the fire starting technique, the coal must be transferred to

something that will continue its life and maintain the heat created

until it is fully developed into a fire structure. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 7

|

In Photo 7, I have collected some cattail from the swamp that I am

standing beside. I harvested and made it like a small blanket. Place the

tinder from the top of the stone and transfer it to the cattail blanket.

This blanket of sorts has its advantages here. It will not only extend

the life of the coal, but will shelter it as well. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 8

|

Photo 8 shows this process happening. Dump the tinder fungus from

the stone into the cattail blanket. It is not hard to see how quickly it

transferred its heat from one coal to the blanket coal. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 9

|

Once this step is completed, Photo 9, close the blanket of cattail

around the coal. This will hold the tinder together, and assist in

extending the life of the tinder fungus piece. This will allow you to

initially use a very small fungus tinder coal on the stone. When the

cattail blanket is closed, any heat generated from the tinder coal, will

be held in the blanket. You will not have to take a long time to realize

how much heat is actually transferred. Your hands will tell you soon

enough!

|

|

|

|

|

Photo 10

|

Open the cattail blanket from time to time and blow a few breaths of air

onto the tinder. Photo 10. This will assist in spreading the heat

on to the piece of cattail. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 11

|

It is now becoming evident that the piece of tinder fungus coal is getting

very small, and the cattail blanket is the host coal. Photo 11.

This happens as the fungus coal gets used up.

|

|

|

|

|

Photo 12

|

What is evident is that most of the initial fungus tinder is consumed.

Photo 12. This whole process has now developed a good coal base that

will be a great fire starting tool after allowing the tinder fungus to

transfer its heat to the cattail blanket.

I have, for the purpose of this article, collected some cedar bark

and taken the time to form it into a "cedar nest." This will now be used

to transfer the cattail blanket right into the center of the cedar

blanket. It will do the exact same thing that we did initially with the

fungus tinder to the cattail blanket.

However, at this stage you will see, by squeezing the cattail blanket

to maintain all of its warmth, and by gently blowing on the cedar

blanket, it will blow into a flame with a few good breaths and some

patience.

|

|

|

|

|

Photo 12a

|

I have, for the purpose of this article, collected some cedar bark

and taken the time to form it into a "cedar nest." This will now be used

to transfer the cattail blanket right into the center of the cedar

blanket. It will do the exact same thing that we did initially with the

fungus tinder to the cattail blanket. However, at this stage you will see, by squeezing the cattail blanket

to maintain all of its warmth, and by gently blowing on the cedar

blanket, it will blow into a flame with a few good breaths and some

patience.

|

|

|

|

|

Photo 13

|

At the beginning of this article, I mentioned the use of fungus

tinder. The side you see is the side against the tree. When you look for

birch trees, and wish to find some of this tinder, you will see the

black side of this fungus, which is the outer side. Photo 13

shows the yellow birch tree that I harvested this particular piece of

fungus. Remember: when you remove such a big piece from the tree, it is

be a good idea to collect some sap, and fill in the wound on the tree.

My policy has always been: "If you use something from the earth, try to

add something back to the resources." |

|

|

The tinder fungus as it was

harvested from the birch tree. |

|

|

|

|

I use this technique for fire starting most of the time. I find it

practical, in most environments, and if the available materials are not

too hard to find. It has been a good fire starting technique for me, and

there have not been many times when it has failed to produce a good coal

to get my fire going.

Whatever useful method you choose to use, take the time to try it in

all weather conditions. Then, practice, practice, practice! It will pay

off. |

|

|

|

All photos and text are Copyright Allan "Bow"

Beauchamp.

This article originally appeared in Wilderness Way magazine, volume 8,

issue 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|