|

|

|

|

Home →

Survival →

Navigation

Natural Navigation, Part II

by

Allan "Bow"

Beauchamp |

|

|

|

The previous article contained the first installment about

natural navigation. Readers of that piece understand how this

basic skill could mean survival in the bush in an emergency

situation. The first article established some easy-to-observe

ways that nature assists us in finding our direction -- if we

only take the time to learn. I also stressed that all

findings/practice runs must be verified with a compass until you

are absolutely confident of your accuracy in reading natural

signs. There is always the exception to the rule, so be alert.

If you spent time in practicing these skills -- dirt time --

then this installment will bring its own rewards. We're now

going to spend some time on our hands and knees. Careful, close

observation will greatly increase your ability to observe

natural signs at a much greater distance. I am still amazed how

much I learn every time I go into the swamp or bush. Small

things will catch my eye, and I have to go and see it for

myself. Nature is truly amazing! |

|

|

|

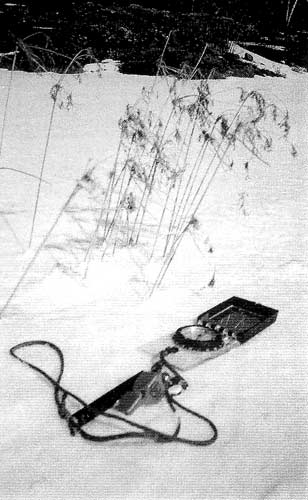

Photo 1

|

Let's look at photo

1. First, we see the windswept grasses. We

remember from the first article that the prevailing

winds are from the northwest in this area (northern

Ontario, Canada). (You will have to ascertain the

prevailing winds for your own area.) |

|

|

This seems to indicate to us that we are looking from a northern

direction. Secondly we see shadows, and we know that the

direction of shadows is also an indicator. Does this confirm our

first conclusion? The shadows are close to the little poplar

saplings and fall to the left side. Based on the time of day for

this photo (early afternoon), this confirms our initial

findings. We are indeed standing north of this photo, facing a

southern direction. What else can nature tell us here? At the

bottom left hand corner of this photo, we now see some pitting

in the snow. The constant sweeping action of the plant (with the

prevailing winds) will smooth the snow away from the plant. This

again confirms our decision regarding the prevailing winds for

this area, and thus the direction these plants indicate. |

|

|

|

Photo 2

|

In photo 2,

what is evident? Look at the direction small grasses

point in the wind. Also, in the background, we see a

rock. The snow has melted from this side. From the

last article we remember two things about rocks:

that the hottest (southern) side will have snow melt

first, and that lichens prefer to grow on the

hottest/southern side. The compass in the photo

confirms our findings (the mirrored end is toward

the north). When looking for natural indicators,

we want to look at both the foreground and

background, near and far, and use two or more

techniques that compliment the other. Using many

natural indicators gives us the greatest certainty

of coming to the right conclusions.

Remember the hands-and-knees time promised you?

Let's look back at photo 1 and see if we

missed anything. At the bottom of the plant, we see

how the snow is being mounded at the base of each

little plant. (When viewed up close, on your knees,

this would seem more prominent.) This snow is piled

as a result of the prevailing winds. Does the side

that faces the sun (south) have less snow? You

should now start seeing how all are connected. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 3

|

The three little

plants in photo 3 have much to tell us if we

stop to observe. First and foremost, we see a

shadow. Knowing the time of day, this is an obvious

clue. If at this point you still need the compass,

it is okay; soon this should be elementary. When

we examine the snow beside the plants, we see that

it has formed a natural ridge. This assists us in

seeing the prevailing wind direction. Now as you

walk across the windswept areas, you will have

something else to view and add to your list of

natural indicators.

At the bottom of these three plants, we again see

that the snow is more on one side than the other.

Now the terms "windward" side and "lee" side have

new meaning for the navigator. If we again study our

little indicators closer, we will see small

particles that have fallen from this plant and will

blow away in the wind; these will be on which side?

Again these small, minute indicators are best viewed

from as close as you can get to them. While walking

past, pause for a minute on one knee and you will

gain insights into these as direction indicators. |

|

|

While the shadow was the most obvious indicator, it was

dependent on a sunny day. The snow ridging and blown

seeds/particles would have been evident any day or at night with

artificial light. Let's talk about the shadow again. Are the

shadows cast by these three plants short or long? Can we use

this as a time estimator? If you were to recall from the

previous article, we know that the sun this time of year follows

a southeast to southwest path. If we stayed at the three plants

all day, we would observe the sun being cast along a line from

west to east past the plant. As mentioned in the previous

article, this was the basis for the shadow tip method. But this

would take a full day and, at this point, we want to examine

some techniques for short observation stops. It is possible we

can simplify this technique to save some time? Will we still be

accurate? Let's say we use the little ridges in the snow as a

quick direction indicator following the same principles as the

shadow tip method. When we view the compass we can see that the

snow-formed ridges were made as the wind swept along the surface

of the snow in the northern direction. The sun has cast a shadow

over our little plant, and we observe this to be in a westerly

direction.

As the sun rises in the east, the first shadows will be cast

towards the west. (Is this a hint as to the time of day for this

photo?) Since we are so far north, and the sun shines from the

southeast to southwest as the day progresses, all shadows cast

will move from the northwest to northeast as the day progresses.

The shadow we see is on the westerly side and the windswept

ridge formed from the prevailing winds is in a northerly

direction. This will give us our walking shadow tip method. |

|

|

|

Photo 4

|

What if you're where

you can see nothing but snow? Photo 4 has the

answer. Here you see a snow pile made for training

purposes. Look, an instant shadow indicator. While

your body obviously also casts a shadow, it is not a

stationary object. To mark the path the sun is

traveling, you need a stationary object. This has to

be the easiest-to-make indicator ever. |

|

|

|

|

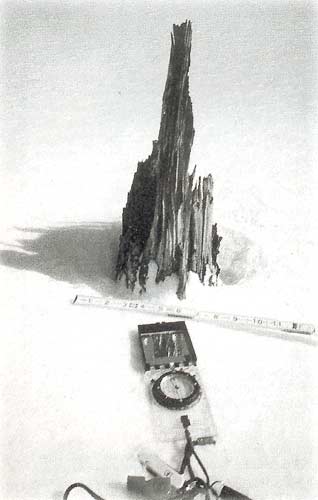

Photo 5

|

Photo 5 shows a

stump. As this is early in the day, the shadow is

cast to the west. What if I hadn't told you the time

the photo was taken, could nature provide us with an

answer? Well, let's find out. The stump here is a

very plain stump, nothing special, right? Well, the

shadow being cast by it points to the west, or does

it? Because the compass says so? What if my compass

was sitting on a big mineral deposit just under the

snow? Let's prove that all things are working

correctly.

One thing I would always stress is don't trust

just the one thing. Trust the many things. That will

give you the right answer.

First, the stump has more snow melted on one side

as opposed to the other. This can be confirmed with

my folding ruler. We know that the sun is hottest on

the southeast to southwest side. This will cause

more melting on that side.

Secondly, as the sun rises in the east, the

shadow gets cast to the west. If the shadow is being

cast to the east, then it will be an evening shadow.

If the shadow is more of a circle formed around the

bottom of the stump, this concludes that it is more

around noon. Simple, Ah! No magic, just observing

nature's indicators. |

|

|

My hope is that now you are starting to see some of the small

natural indicators that you would have previously overlooked. A

natural navigator sees much more than the casual, untrained

observer. |

|

|

|

Photo 6

|

Photo 6 is

somewhat dark but has something to offer. What do we

see? Just two footprints, one from a man and one

from a moose. What could these possibly tell us

about direction or time? The man's footprint is

from my size eleven shoe. The moose's shoe size is

harder to guess. Just trust me when I say he is a

"big" bull moose. If you hang around the swamp much,

you will be amazed at what nature will show you.

This bull moose and I play a trailing game

year-round. Anytime I come to the swamp to study, we

are trailing each other.

The tracks show a shadow, but this time it is a

sub-surface shadow.

Now you are getting the idea of how small and

detailed you can be to navigate. As a natural

navigator, you should not overlook even the smallest

of details. Up until now, you have seen natural

indicators from walking by or by being on your

knees. To really see some, however, you will have to

spend a great deal of time on your stomach.

What can we learn from a sub-surface shadow? At

the back of my track, we see a small shadow. As the

sun will be from the southeast to south west, this

indicates that the track is heading in a northern

direction.

|

|

|

A moose is a very large animal, especially an old bull, so we

have a larger impression to study. Examine this huge print.

Remember that objects tend to be hotter on the side that faces

the sun, which is the southeast to the southwest side. The huge

print seen here is starting to distort in the heel area,

agreeing with the conclusion drawn from the human footprint that

the heel is the southern side of the footprint. This is also

supported by the shadow within the moose track. Once again, I

encourage the reader to go into the bush and practice. Only then

will you truly see what I am trying to convey. Nature will teach

you something but you have to go into her classroom to learn it.

Article and Photos Copyright

©

Allan "Bow" Beauchamp.

This article originally appeared in

Wilderness Way magazine,

Volume 5, Issue 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|