|

|

|

|

Home →

Survival →

Navigation

Natural Navigation, Part III

by

Allan "Bow"

Beauchamp |

|

|

|

This installment will offer more natural indicators for

orienting yourself in the wilderness and reinforce the reasons

of what, why, and how to see. We have established a multilevel

proving system that will help you become more accurate in

determining the directions, north, east, south, and west. Each

time you walk into the bush, do a primary test to gauge these

skills.

The first article was to help you identify nature's

indicators and be less likely to get lost when separated from

your equipment. The second article showed some exceptions to the

rules. As in the previous installments, the reader is encouraged

to do their own "dirt time" -- time in the bush, on your belly

if necessary, looking at the clues nature provides as to

directions. Learn to read nature, check it against your compass,

be mindful of exceptions, practice in good and bad conditions

and with and without sunlight, and internalize your own system.

Now is the time to test your knowledge and skill level. Only

practice will help you develop true confidence.

Now in this part of our training let's continue to see

natural indicators. Again, snow is used as a backdrop as it

shows so many small indicators prominently, making it easier for

the reader to see what I am trying to convey. Most readers

probably won't have snow, but you can use these natural

navigating techniques all year around, in all types of terrain

and all types of weather. |

|

|

|

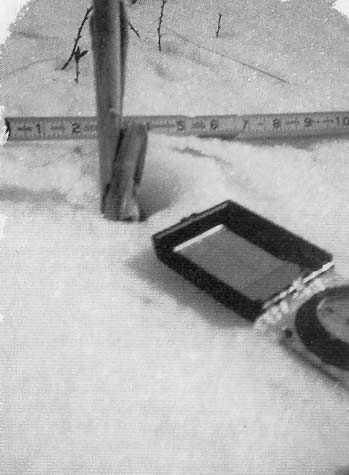

Photo 1

|

Remember the moose

track (Part II, photo 6)? Some of the tips learned

there will apply to objects 100th that size. In

photo 1 you will see a cattail stalk beside our

compass. The compass is set so that north is to the

mirrored side. To view this scene in the wild, you

would want to be as close to the ground as possible

(yes, on your belly). While viewing the cattail

picture, ask yourself, "What is this telling us?"

Let's ignore the shadows for now, as you want to see

much deeper.

At the top left corner we see some snow crest.

This is caused from the wind, and will assist us in

determining directions. Just as our moose track

offered sharp edges and depth as natural navigators,

all the small changes on the snow surface will mean

something of benefit to our determining the

directions. Our focus now is beyond just what we see

and into what we feel. Try not to just look at these

photos -- imagine you are at the sites with me.

Looking at the cattail base, we see that the snow

has melted more on one side than the other.

Remembering the previous articles, we know the sun

caused this as it moved from a southeast to

southwest direction. Now think if you will of taking

the cattail out of the hole and running your fingers

around the edges of the depression. Is there a

difference? What would we feel? Will the windward

side be sharper than the windless side? |

|

|

If we were to lie on our bellies and view the hole from the

ground level, would we see a slight difference in the windward

side of the hole (northwest side) as compared to the opposite

(southeast) side? For additional support of this theory, all we

have to do is look at top of the photo and view the long piece

of grass that has come loose on the snow, north of the cattail.

It would be very easy to sense the difference in how the snow is

blown if you could remove the grass and feel the snow. Which

side would be smooth and which side would be sharper?

Examine the snow crest at the top left again. Here the wind

difference is more pronounced. The rougher side is formed as the

wind sweeps upwards, causing a sharp edge. If you could get down

on the snow within an inch from the cresting, it would seem very

pronounced. Another test is by feeling. Close your eyes and feel

all the sharp edges and all the graininess around the entire

surface. Then feel how the windward side contrasts with the

windless side. Now then, open your eyes and view the cresting

from the wind side and again from the windless side. Stand up

after you view this and start to back up until you lose sight of

the small cresting. You will find this amazing, as to how far

you can view this small indicator from nature when at first you

would have passed this by.

If you notice a similar cresting when walking across a snow

covered lake, go on the side of the lake away from the sun and

view it, then view it from the side of the lake facing the sun.

When facing the sun, the cresting is more pronounced as we have

determined earlier.

We can use this same cresting indicator on a moonlit night.

As the moon also rises in the east and sets in the west, the

moon's shadow will highlight small indicators.

Why worry about minute indicators you have to feel? What if

you were to go into the bush at night, collecting wood south of

your camp, and suddenly you get a tree limb whipped across your

eyes, temporarily blinding you ? Could being on your hands and

knees and feeling these small indicators offer any assistance in

your time of need? Would a compass be of any use here? If you

were caught in a sudden storm and visibility was diminishing

fast, could you feel the base of the cattail and know which

direction would get you back to camp?

How about that moose track, or perhaps a deer track you find

if turned around in the woods? Could you look for the shadow in

it? Would it confirm your direction or perhaps be a time

estimator? In photo 1 we see that at the base of the small plant

the cresting is very pronounced. Again, get low for the best

view. Spend the time examining the small differences around the

plant closely. The better you understand every detail, the

farther away you will recognize these indicators. |

|

|

|

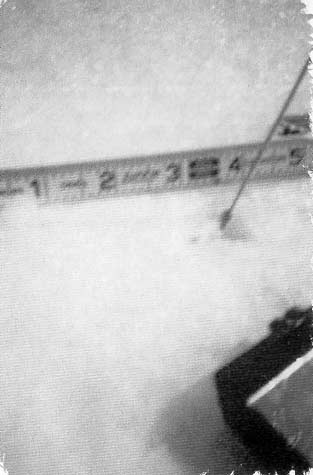

Photo 2

|

In photo 2 you

can see a closer view of the base of the cattail and

the differences from one side to the other. The

measuring tape helps illustrate the distortion from

one side to the other. Again, as with the moose

track in the last article, there is a "leaning"

towards the southern direction. Remember that the

prevailing wind in this area is from the northwest.

In the background behind the cattail stem, you will

see small twigs that have also succumbed to this

wind. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 3

|

Even smaller than a

twig, a single blade of grass in photo 3,

serves to guide us. Again, the compass is set with

the mirror in the northern direction. Obviously, the

smaller the guide, the closer we will have to get to

see and feel all that nature has to say here. |

|

|

|

|

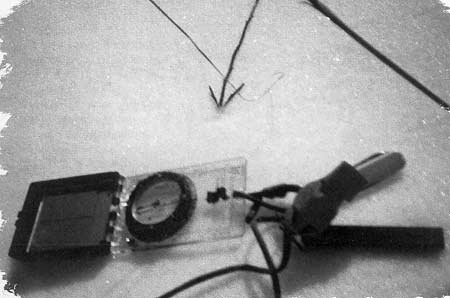

Photo 4

|

In photo 4 we

see a more detailed view of the wind working the

surface. Notice the differences in the surface. The

more attention we pay to very fine detail, the

easier it is to hone our viewing skills and

determine our direction more accurately. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 5

|

In photo 5 we

see beside our compass a small piece of grass that

has blown back and forth all day. The wind has

caused this small grass to etch a mark into the

snow. If you stopped for a five minute sitdown on

your long journey, would you be aware of this small

indicator? You should be aware of it now. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 6

|

In photo 6 we

see this small natural indicator highlighted with

our arrow pointer. When you are on the ground

resting, they should be easy to see. I have been

quoted as saying "you should be able to go into the

bush at any time, no matter what the weather or the

time of day, and find ten natural indicators to

guide your path." |

|

|

|

|

Now when you look back at previous articles' examples, ask what

more you see in them. As the lessons have progressed and you

have practiced, more small details will become obvious. I have

been trying to give you something to mentally visualize. Now it

should start to become easier. Take the time to review this

series, starting with the question of why natural navigation is

important. What benefits does this offer me as opposed to

manmade tools? When you did your first practice test, what was

the result? Now do the test again, and see what you have

learned.

I first showed you how to view natural indicators in passing.

Then I talked more of the short stop type of indicators and told

you about a variety of techniques and how they could be combined

to confirm each other and provide you with more options. This

would maximize your opportunities for a safe trip home. With

this article, I tried to make you more sensitive to the minute

changes around you.

With this in-depth approach I tried to interest you in

feeling the changes so as to better visualize and experience

these yourself. All of these techniques are, of course, no good

to you if you do not go into the bush and develop your own feel

for these ever-changing natural indicators. Practice will

increase your accuracy immensely.

You weren't born with a "sixth sense". However, as you learn

to natural navigate, you can walk around the bush with your

friends and tell them the direction accurately with no manmade

tools. I wonder what they will say ...

I hope you have gained a more in-depth view of nature's

mini-navigators, which you can put into your own cache of

experiences. Nature will never steer you wrong.

Go out into whatever kind of bush you have and look for clues

as we have tried to demonstrate here. Soon you will see that

even if the vegetation is different, the indicators are always

there. You will have to go and seek them out (dirt time). Start

simple. Notice the easy indicators first. Then go to

"multi-leveling" to determine if they confirm each other for

better accuracy.

When you walk through the bush after a storm and come across

a deer bedding spot, take your compass out and confirm what you

will probably now know. On the same walk, after a storm, look

around and note if all the trees are wet on one side. If there

is a distinctive dry vs. wet side to trees, you will know the

prevailing wind direction for your area. Once the direction of

the prevailing wind is known, this is an easy indicator for the

bush traveler to follow. Is the bark on the harshest weather

side going to be thicker than the side that isn't as harsh? Do a

test. Go experience this.

Remember lessons from sunlight in the earlier installments.

If you took that wet tree and cut it down, would the rings of

the tree be thick on the side that gets the most amount of

sunlight during the day? Always remember to combine indicators

for the best result.

Article and Photos Copyright

©

Allan "Bow" Beauchamp.

This article originally appeared in

Wilderness Way magazine,

Volume 5, Issue 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|