|

Back in MOTHER NO. 71,

wilderness survival expert Tom Brown 7r. (known worldwide as

The Tracker) showed us how to construct the leaf hut-an

expedient and reliable short-term survival shelter. In this

article, the ninth installment of The Tracker's ongoing

wilderness survival series, Tom discusses the basics of

building two different long-term survival

shelters.

|

| A

thatch "shingle" made from a bundle of long-stemmed

grass wrapped together at the root ends with cordage

. |

|

| A tipi-shaped thatched hut such as this can be

built in a day and can accommodate an elevated sleeping

loft and provide two adults with spacious three-season

shelter. |

|

|

| The author calls mud huts like these "the finest

survival shelters I know of". His favorite style is a

lean-to with a roof that slopes down to the ground at

the rear. |

|

| The basic framework for a thatched

hut. |

|

| Thatched bundles are installed from the bottom up

in overlapping rows, much like roofing

shingles. |

|

| When constructed properly, a mud hut can be a

reliable year-round dwelling in any climate. Cool in

summer and warm in winter, the structure will withstand

rain, wind, and heavy snow. This "earth shelter" hut

provides survival living at its

finest. |

With many hunting seasons opening

in the coming months, a lot of individuals—some of whom have

had very little wilderness experience—will be taking to the

woods. Unfortunately, a few of them will also become lost or

be stranded by inclement weather. Should you be faced with

such a wilderness survival situation, your first course of

action should be the construction of a temporary shelter—such

as a leaf or debris hut—that will keep you warm and dry and

that can be erected quickly, with a minimum expenditure of

energy and natural materials. Only after that basic shelter is

up—and your

other pressing survival needs (water, fire, and food) have

been taken care of—should you consider building a larger, more

permanent and comfortable wilderness home.

Of course, if luck is with you, you'll

never need to erect and occupy either of the two long-term

survival shelters I'm going to talk about in the following

paragraphs. But if you ever should find yourself stranded in

the wilds for an extended period, knowing how to construct a

shelter that will not only keep you warm and dry but also

provide ample living and work space could brighten your

outlook considerably—and by doing so, increase the likelihood

of your surviving until you're rescued.

Neither of these advanced shelters

requires any construction tools other than those you can

fashion yourself, and no materials other than those provided

by nature. Also, once erected, either style of shelter should

be habitable for several years if kept up. In fact, if you

have access to a privately owned woods (your own or a

friend's), you might want to build a "practice" survival hut.

It could serve as a storage building or even a primitive

hunting camp or blind; it'll cost nothing to erect, will blend

in with its natural surroundings, will be relatively easy to

construct, and—most important—will provide invaluable hands-on

experience that will stand you well should you ever wind up in

a true long-term survival fix.

PLAN BEFORE YOU BUILD

No matter what type of shelter

you're building, long-term or temporary, locate it on a

well-drained, elevated site that's at least 50

yards from any body of water that

could rise and flood you out. And while it's beneficial to

have your shelter shielded from the elements by such natural

windbreaks as large trees and rocks, don't place your survival

home so deep in the forest that sunlight can't get through to

warm and brighten it. Finally, consider the availability of

construction materials and other survival necessities (such as

water) before deciding on a building site; hauling materials

in from long distances is a waste of time and—more

important—precious energy.

THE THATCHED HUT

Thatched huts are commonly used as

year-round dwellings in tropical and semitropical climes, and

can offer satisfactory shelter for spring, summer, and fall living in

temperate zones. If properly constructed, these seemingly

fragile structures can withstand high winds and prolonged

downpours and will provide excellent protection against the

heat of the baking sun.

The only possible skill-related obstacle to building this shelter—unless you always

carry some type of rope with you—is that the hut's

construction requires several yards of cordage (that

is, any rope, cord, or twine fashioned by hand from natural

materials) or long strips of inner bark from certain types of

trees. (See my article "Making Natural Cordage" in MOTHER N0.

79 to learn this important survival skill.) Once the cordage

is at hand, however, a thatched but goes up in as little as a

day and can last several years if properly maintained.

I prefer a tipi-shaped but that's tall

enough to accommodate an elevated sleeping loft; it leaves

plenty of room on the ground floor for storage, working, and

moving around. For two adults, the optimum size for a

tipi-shaped thatched but is nine feet across the base and ten

feet high. While long-stemmed grasses make the best thatching

material, reeds are also excellent—and cattails, ferns, and

evergreen boughs will suffice if nothing better is available.

To construct a thatched hut, locate

several long, stout saplings that can be placed upright in a

typical tipi shape. These upright saplings should be strong

enough to hold your weight (you'll have to climb on them

during construction) when their butts are spaced evenly around

the diameter of the hut's base. (I recommend sinking the butts

a few inches into the ground to increase the structure's

stability.) Before standing the poles up, lash their tips

together by wrapping them with cordage where they will cross

at the apex of the tipi (Fig. 1).

The next step is to

weave parallel hoops of long, flexible saplings horizontally

between the upright tipi poles to form a latticework,

securing these crossties to the uprights with square-lashed

cordage (Fig. 1, Inset A)

The first (lowest) round of

horizontal crossties should be located no more than a few

inches above the ground, with subsequent rounds spaced at even

intervals up the tipi poles. To insure that the overlapping

rows of thatch will provide a proper shingling effect, the

vertical spacing of the crossties should be no more than half

to two-thirds the length of your thatching material. (For

example, if you'll be thatching with bundles of grass that

average 18" long, the horizontal cross-ties should be

positioned at 9" to 12" intervals up to within a few inches of

the top of the hut.)

To provide for a door, omit enough rows

of crossties between two of the uprights on the east-facing

side of the hut—beginning with the bottom round—to form an

entrance hole just large enough to crouch through.

The final frame members to be put in

place are several sturdy poles (rigid, large-diameter saplings

do nicely) that will act as floor joists to support the

sleeping loft. Since they'll have to support your weight, the

loft joists should be securely lashed directly to the uprights rather than laid atop a

round of crossties. For loft flooring, you can use overlapping

sections of heavy bark, or make a mat of smalldiameter poles

laid side by side and perpendicular to the joists and lashed

in place with cordage.

THATCHING

To make a thatch "shingle," gather

up enough long-stemmed grass to make a bundle that's a little

too fat to hold in one hand. Now turn the bundle so that the

root ends of the grass are facing up, and "belt" it with

cordage about a quarter of the way down from the top. Wrap the

cordage tightly enough to form a waist in the bundle, and tie

it securely—but leave enough line dangling from either side of

the knot to secure the bundle to the framework of the but

(Fig. 1, Inset B).

Once you have a quantity of thatch

bundles made up, tie the first one—root end up—to the bottom

crosstie and snug it alongside the nearest upright. Attach the

second bundle hard against the first, and continue in this

manner until you've thatched the lower crosstie all the way

around the but (except for the door opening). Now begin

thatching the next cross-tie up . . . then the next (using the

framework as scaffolding), until you reach the top of the

tipi. The critical point to remember is that the bottoms of

the thatch bundles in each higher row should overlap the tops

of the bundles in the row just below it—exactly like shingles

on a roof.

The uppermost round of thatching will

form a bushy cap at the top of the tipi. To make this cap

watertight, tie the tops of the uppermost layer of bundles

together with cordage. To further waterproof the crown, you

can lash several more bundles of thatch over the

top at different angles.

Now, with your outstretched fingers, go

over the thatching inch by inch, working the bundles of grass

until they intertwine and lay flat to provide a wind- and

watertight surface.

The entrance hole can be draped with

animal hides, or a door fashioned by lashing bundles of

thatching to a stick framework.

The final step is to reinforce the entire

shelter by spiraling cordage down from the top to hold the

grass bundles flat against the framework and to prevent them

from flapping and separating in high winds (Fig. 1, Inset

C).

THE MUD HUT

The mud but is one of the finest

survival shelters I know of—because it's suitable for

year-round habitation in any

climate. Wind doesn't make it shake, it's strong enough to

stand up under heavy snow loads, it tends to be warm in winter

and cool in summer, and it's easy to maintain.

What's more, because a fireplace can be

safely built inside this shelter, it's especially well suited

to riding out severe winters in relative comfort. You can

design and build a

mud but in just about any shape you can dream up, and

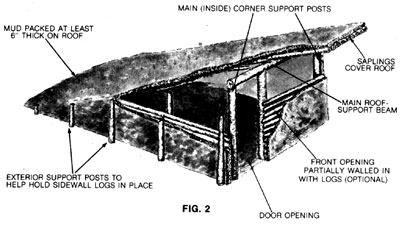

make it as large or as small as you want, but my favorite is

what I call the mountain man style: a lean-to with sides, a door on the high end,

and a roof that slopes back and down to touch the ground at

the rear of the shelter (Fig. 2).

The load-bearing members of the but are

rocks and logs, but the material that holds it all together is

mud. Not just any old mud, though; you want the thickest,

gooiest muck you can find. You can make your own by mixing

clay-bearing soil and water, but it's better, if possible, to

locate your shelter near a natural deposit of muck (common

along the shores of lakes and slow-running streams and in

swampy areas).

In addition to logs, rocks, and mud,

you'll need a good supply of dried grass to mix with the mud

as a binder.

Begin construction by cutting several

very sturdy poles to serve as the uprights that will support

the roof and act as a framework for the sidewalls. Doing the

best you can with the tools you have available, sharpen the

thinner ends of the uprights and cut V notches in the butt

ends. (If you can locate enough of them, forked poles—with the

tines facing up—make the best upright supports.)

Now drive the sharpened ends of the

uprights a foot or so into the ground; the two thickest and

tallest poles should form the front corners of the lean-to,

with additional uprights spaced down the sides of the

structure. (The exact number of vertical supports you'll need

will be determined by the size of the hut.)

A single horizontal log beam spans and

rests atop the two tallest (front) uprights. Since this beam

will have to support the considerable weight of the front of

the roof, it should be hefty and should be lashed firmly in

place to the notched (or forked) tops of the uprights.

To fabricate the roof, lay small logs or

stout saplings side by side and parallel to the hut's

sidewalls—their tips jammed into the ground at the back

(lower) end of the lean-to, and their butts overhanging the

front roof beam by at least several inches (the more the

better, as this overhang will help shield the door opening

from sun, rain, and snow). If you have plenty of cordage

available, lash the roof poles together, as well as to the

uprights at either side and to the crossbeam in front.

The sides of the mountain man but can be

built up (that is, filled in) with either rocks or logs—and

here's where the going gets muddy. Start by preparing a muck

pit: I find that two parts thick mud to one part dried grass

provides a good general-purpose mortar. When the mud is ready,

mound up a row of it on the ground where the first sidewall is

to go, then press the first log (or the first row of large

rocks) firmly into the mortar. Now spread another layer of

mortar along the top of the log (or rocks) you just put in

place, and lay on the second log (or the second layer of

rocks) . . . and so on until both sides of the but are

enclosed all the way to the roof. Because of the triangular

shape of the sides, the logs (or rows of rock) will get

shorter as the walls rise.

If you're siding with rock, the walls

will be stronger if they're made thickest at their

bases, narrowing as they rise. If you're siding

with logs, stack them up and mortar them in place snugly

against the outsides of the upright support poles—then pound a

second row of uprights into the ground just outside the

horizontal logs so that each wall is sandwiched between two

rows of uprights.

Finally, coat the exterior and interior walls with a heavy layer of mud to

seal any cracks . . . and pack it at least six inches thick on

top of the roof to provide weatherproofing and insulation. (If

you build your but in the spring or early summer and cover its

mud top with a few inches of loose soil, the roof will

probably grow a matting of grass and weeds, increasing its

durability significantly.)

A mud shelter will require several days

to dry thoroughly, depending on the weather. Surprisingly,

though, rain doesn't seem to slow the drying process to any

extent or to wash away much of the mud.

HUT HEAT

A covering for the open front of

the mountain man but can be fashioned by suspending animal

hides from the top of the opening—or you can enclose most of

the front with mud and logs or rock, then make a sturdy door

for the remaining opening by lashing together several large

saplings or small logs cut to length. (If you have no tools,

you can "cut" logs by burning them in a campfire at the

desired point of separation, then hacking at the charred wood

with a large, sharp-edged rock.)

To take care of your heating and cooking

needs, you can use rocks and mortar to construct a fireplace

and chimney—which can be built on either the outside or the

inside of the structure. An external fireplace necessitates

cutting a hole through one wall at floor level, while an

internal fireplace takes up living space and requires cutting

a hole in the roof for the chimney.

AT HOME IN THE WILDERNESS

The thatched tipi but and the

mountain man mud but are but two examples of the many ways you

can make yourself more at home in the wilderness. In practice,

there's no limit to how well you can care for yourself in a

survival situation—if you'll only accept the responsibility of

gaining the necessary knowledge and skills now,

before you need them.

For more material by and about Tom Brown Jr. and the Tracker School

visit the Tracker Trail

website.

|