|

Now in most parts of North America, the most

easily collected survival foods are wild plants. However, since many

native vegetables aren't available in the winter months (and because

most regular MOTHER-readers already have a pretty fair grounding in

edible plant indentification), I've decided to discuss methods of

gathering animal foods here. And the techniques that I'll

focus on are hunting (with a simple throwing stick) and trapping.

HUNGER IS THE BEST

APPETIZER

Naturally, when eating is a matter of life or

death (as it could be if you were stranded for an extended period of time), an individual can't allow his or

her dietary preferences to get in the way. You should know, then,

that virtually all mammals are edible (in fact, when skinned and

cleaned, very few animals can't be safely used as food). It's

important, however, to avoid eating any creatures that show signs of

sickness . . . and, if possible, to cook all meat (usually either on

a spit or in a crude stew) until it's well done. Remember, too, that

such protein sources as grubs, grasshoppers, cicadas, katydids, and

crickets shouldn't be passed up!

THE MOST PRIMITIVE

WEAPON

A basic throwing stick is, quite simply, a

sturdy hunk of branch. The optimum size and shape will vary

somewhat, depending upon personal preference, but I like a stick

about 2-1/2 feet long and approximately half as thick as my wrist.

Of course, some primitive peoples have turned the making of throwing

sticks into an art form (consider the Australian kylie, or hunting

boomerang, which is carved to an aerodynamic profile that actually

allows it to fly farther than an unshaped stick of similar size

and weight could be thrown). But for our purposes, we'll be

discussing the handling of a weapon that requires nothing more,

perhaps, than being broken to a comfortable length before it's put

to use.

Such a basic club can be thrown either overhand

(when, for instance, you're trying to knock a squirrel from the side

of a tree) or sidearm (when you're in an open area, where brush

won't interfere with the stick's flight). In using the first meth

od, point your left foot at the target (if you're a right-hander

southpaws can simply reverse these directions). Then, holding the

smaller end of the stick loosely in your right hand, bring the

weapon back over your shoulder and hurl it, with good end-over-end

spin, straight at the mark. At the moment of release, your

shoulders should face the game squarely.

The sidearm throw is similar to the motion used

in stroking a tennis ball with the racket. Point the left toe at the

animal, bring the stick to a cocked position at your side, and throw

it . . . squaring your shoulders and snapping the club—as if you

were cracking a whip—to give it spin.

Always be sure to carry your throwing stick

when away from camp for any reason. Not only is there a chance that

a small bird or animal will suddenly appear within range, but

there's also the possibility that you'll encounter other food

sources (say, nuts or fruit) that can be knocked down with the club.

I don't have the space to go into any detail

about stalking techniques here. In general, you should avoid any

abrupt movements . . . walk slowly, feeling the ground (or, perhaps,

a brittle twig?) beneath each foot before putting your weight upon it . . . and try to time your

movements to coincide with the feeding patterns you observe in your

quarry (most animals will alternate regular periods of feeding with

pauses to survey their surroundings for danger). Remember, though,

that this is a very rudimentary outline, and that—as always—the time

to practice this particular survival skill is before you need

it.

THE THREE TOP TRAPS

There are probably well over 100 traps that can

be fashioned-using primarily foraged materials—in a wilderness

setting. But although any student of outdoor survival would be well

advised to acquaint him-or herself with as many designs as possible,

I consider the rolling snare, the figure 4 deadfall, and the Paiute

deadfall to be the most easily made and versatile of the

lot.

A snare, as you may know, is little more than a

noose—fashioned from wire, string, sinew, or handwoven

cordage-positioned in such a way that it can "lassoo" an animal. The

rolling snare, in particular, is placed directly along a

well-traveled animal run or trail. When the beast unknowingly puts

its head through the loop, the trigger is released, and a sapling-to

which the noose is tied-whips upright, often breaking the animal's

neck and thus killing it instantly. You must, of course, be

selective when choosing a site for your snare . . . if it's set on a

trall that's used by animals larger than those you're after, they

might blunder into, and destroy, the device.

The rolling snare is one of the easiest

survival traps to set up. And, because the pressure points on the

trigger mechanism (as illustrated in the accompanying photos) are

rounded rather than squared, it's not likely to freeze up during

cold weather. Be careful, though, when setting this or any snare

that depends upon a bent tree for its power, as the sapling could

unexpectedly spring up and catch you in the face.

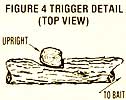

THE FIGURE 4

DEADFALL

A deadfall is a baited trap which, when

triggered, allows a weight to drop on the animal, often—as the term

implies—killing it outright.

The figure 4 takes its name from the shape of

its trigger assembly and is about as simple to construct as any trap

I know of. The trigger is composed of three sticks, two of

which—when used for rabbit-sized animals—will each be about six

inches long, and the third eight inches (the sizes will vary some

with the type of animal to be trapped). The weight is usually a

large, flattish rock or a log.

The figure 4 trap should be set near trails or

established feeding areas, but—since it depends upon bait rather

than upon a beast's unwittingly stumbling into it—never directly in

a run or line of travel. Remember when assembling it that the

vertical stake should not be positioned beneath the rock or log, that the bait should be attached to

the crosspiece and as far under the weight as is practical, and that

a small fence of twigs around the "outer" portion of the upright can

prevent an animal from inadvertently setting off the device by

striking the trigger while not under the log or rock.

THE PAIUTE DEADFALL

This trap is similar to the figure 4, but has

the advantage of a more sensitive, "faster" trigger. Again, the

upright should be positioned well out from under the lip of the

weight and the bait—on the crossbar—well beneath it . . . and the

trap itself will be most effective if located near an area of game

activity but not actually in a well-traveled run.

As you can see in the accompanying photos, a

piece of string, sinew, or woven cordage will be needed to construct

this trap (some threads unraveled from clothing and twisted together

will usually work quite well). The Paiute is more difficult to set

up than are the other two traps described here, but it's also the

most effective of the bunch.

TRAPPING TIPS

You've probably already gathered that there's a

good bit more to survival trapping than simply constructing your

deadfall or snare in the middle of a convenient field. In order to

obtain the best results with these do-it-yourself game getters,

you'll have to understand a little about animal movement patterns .

. . the dietary likes and dislikes of the beasts you're after . . .

and the different methods of making your structures appear "natural" so the animals'

suspicions won't be aroused.

Your most important task will be to locate

areas of high game activity, generally by "reading" the landscape.

Usually (the wilderness always produces exceptions to human rules)

the most productive areas to scout will be those around sources of

water . . . and those in edge environments, where forest meets

field, field meets meadow, and so forth.

In such a location, you may well be able to

spot specific trails, runs, day beds, lays, and feeding areas. By

doing so, you can place your trap in such a way that it'll have the

best possible chance of being encountered by the animal you're

after.

Trails are heavily used tunnels or paths. When

following such a wildlife "freeway", you should be able to note

animal scat, hair, and such that will indicate the type of creature

most often using the path. Remember, though, that even if deer

tracks-for instance-have all but eliminated any other signs from a

trail, odds are that a number of smaller animals are using it, too.

Wild creatures will follow the easiest route available unless

they're either pursuing or being pursued.

Runs are the smaller arteries that connect

established trails to feeding, bedding, and watering sites . . . and

are subject to change as food and water supplies come and go. Since

each run's use is typically limited to one species, its size will

often provide some clue to the type of animal using

it. (Traces of scat and fur, again, will help you make a positive

identification.) By following runs-carefully, causing as little

disturbance as possible to these potential trap locations-you may be

able to find the areas of animal concentration to which they'll

usually lead.

Day beds and lays are spots in which beasts seek cover and/or sleep.

Beds are generally used quite frequently (though one animal might

well have several of them), and usually appear as well-worn

depressions in the grass or ground. Lays, on the other hand, are

less obvious-often showing up as areas of partially crushed weeds or

brush-and are typically found near feeding sites. The pattern of

beds and lays surrounding a known food source can help you predict

routes of animal travel, and thus choose good locations for your

traps (this is especially true when setting snares, as your quarry

will actually have to run into such a trap to be caught).

Feeding areas-which can be located by careful observance of the signs

described already-will, for herbivorous animals, likely be locations

rich in grasses, clover, and tender new growth . . . or, especially

in winter months, young trees and brush with edible bark, twigs, and

buds.

By examining the food plants in such an area,

it's often possible to determine what sort of animals are feeding

there. A diagonal bite that cuts off a plant stalk at about a 45°

angle is typical of such rodents as rabbits and woodchucks.

Straight, finely serrated bites will often indicate that members of

the deer family have been dining . . . while obviously chewed-upon

greenery is usually a sign that predators have been rounding out

their diets-with a little plant foraging.

You will, of course, want to take special note

of exactly what food seems to be preferred by the species you hope

to catch. Furthermore, it's best to try to locate a favorite snack

that, because it has been pretty much finished off, has been

temporarily abandoned for a second-choice edible. If, for instance,

you note that all of the red clover around a group of woodchuck dens

has been eaten, and that the animals are now resorting to a diet of

grasses, it may be worth your while to scout beyond the 'chucks'

range and-if you can-bring back a batch of that rare clover to use

as bait.

"Naturalizing" your traps, in order to lessen

the chance that animals will steer clear of them, will improve your

chances of making a catch. Leave bark on the trigger assemblies, and

rub dirt on any cut surfaces to prevent them from attracting

unwanted attention. When working on a trap, be sure that your hands

are well rubbed with mint, leek, or some aromatic weed to disguise

the human scent. In the winter, it's sometimes possible to

accomplish the same result by smoking a finished trigger assembly

over a fire, and then handling it with gloves that have also been

well scented with wood smoke. (Some trappers will smear their hands

with scat, or with scent from the glands of an animal caught

earlier. The notion may sound unpleasant to you now, but there's

little room for niceties in a true survival situation!)

Once your traps are naturalized and set, be

sure to check them at least once a day . . . to prevent your quarry

from being stolen by a predator or (in hot weather) decomposing, and

to minimize the suffering of any creature that might have been

caught but not killed. Carry your throwing stick when visiting the

traps. A hard blow to the back of the head will, for most of the

small animals that you'll be likely to catch, result in a quick and

relatively painless death.

LEARNING BY DOING

As mentioned above (and over and over in this

series of articles), the time to fine-tune your survival skills is

before you have to use them. Practice reading

animal signs, locating feeding areas, and so on at every

opportunity. Carry a throwing stick on your hikes and indulge in a

little target practice . . . flinging it at stumps, clumps of grass,

and the like.

You should certainly experiment with making

survival traps, too .

. . but don't leave them set in an attempt to catch animals when

doing so isn't absolutely necessary. For one thing, you would likely

cause needless suffering and death, and -for another-none of these

traps is legal in any state . . . unless the trapper is truly in a

life-threatening situation.

Finally, remember that this article is little

more than an introduction to the subject of survival trapping. Take the

time to visit your local bookstore or library for more sources of

information, look into the possibility of attending one of the

survival courses available, and make the building and refining of

your store of outdoor skills a regular and pleasant part of your

life . . . when you're hunting, fishing, camping, or simply taking a

shortcut across a vacant lot to go to the store. Only after you

develop confidence in your own abilities will you be truly able to

feel at home in the wilderness.

For more material by and about Tom Brown Jr. and the Tracker School

visit the Tracker Trail

website.

|