|

|

|

|

Home →

Survival →

Cordage

Bows Bindings

- Part I

by Allan "Bow" Beauchamp

(go to Part II) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I have, from time to time in the Canadian bush, found that I have been in

need of stronger than normal binding or cordage. I always try to utilize

nature as much as I can, so I use what is available around me. A great

respect for nature is gained by using Mother Earth's bountiful

resources.

I remember one time when I was in the bush in the middle of

winter, and I was in need of some binding or cordage. I use the usual

materials one would expect to find. Shortly, I found myself needing more

binding. I decided that as soon as time permitted, I would start

searching for a more durable alternative for binding or cordage.

I found myself sitting in the bush one cold morning, leaning up

against a willow sapling can scanning the bush line for what might be a

good solution to my problem. Nothing seemed to strike me as a better

answer than what I had been using. I got up to move around a little. As

I was getting up, I realized this little sapling was holding my weight

very well.

I figured, "it must be a tough little tree!" Then I realized, if it

was that tough, how tough would it be for a binding?

I started the process of making a binding by cutting down the side of

the sapling a length of about three and a half feet with my small knife.

(An exact length at this point really does not matter, but this will

give you some idea for a good starting point.) |

|

|

|

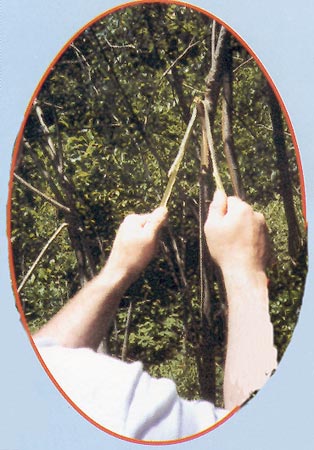

Photo 1

|

In Photo 1, you will see a piece

of cut sapling bark with the inner side showing. I am folding this

piece of cut bark in half lengthwise. This will strengthen it. I try

to keep both halves the same width while I am folding it, as this

will distribute the weight more evenly, and allow for a stronger

piece of binding. |

|

|

|

|

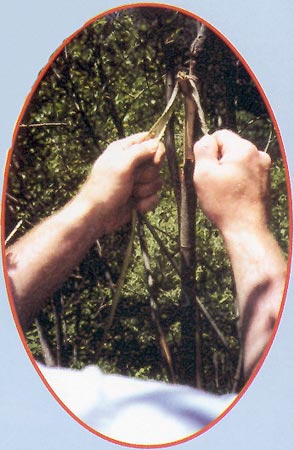

Photo 2

|

Next, I remove another piece of sapling

bark (Photo 2) and use the same process of folding it in half

lengthwise. You can see that I have laid the first piece over a

small branch stub (you have to be able to remove the binding from

the branch once you've made it!). I try to find a small branch at

about eye level to work with when forming my binding. This will help

to give your arms less strain when you are first learning this

process. It will also allow you to see what you are doing easier. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 3

|

Photo 3 shows more cut pieces of

willow sapling bark. I am now ready to begin the next phase. The

number of pieces you choose to use will depend on which type of

binding you want to make. At first we will make an all-purpose

simple, single, strong binding. Once you have practiced and have a

real feel for making binding, I will explain some more options.

Later, I will even give you some insights as to how strong this

binding will be. For now, we will continue with the developing stage

of our binding techniques. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 4

|

We are now ready to start the twisting

segment. In Photos 4 and 5, I am using "one" single piece of

the willow sapling bark. I have folded this strip of bark in half

and draped it over a branch stub. Working with the right-hand side

first, I start twisting this side to the right (I always say, "start

right -- twist right"). This is awkward at first, but stay with it,

and you will see the advantage of this labour soon enough. I twist

this piece of bark until there are approximately 5 or 6 tight

twists.

|

|

|

|

|

Photo 5

|

Using your other hand to hold the

tightened twists is very important. Otherwise your binding will be

too loose.

Once the right side is as tight as you can comfortably make it,

hold it in place and start twisting the left-hand piece of bark.

Repeat the same process as you did with the right-hand side,

remembering that the left-hand piece also gets twisted to the right

-- the same twist as the right-hand piece. |

|

|

|

|

When you have completed both side (the same tension and twisted distance

-- approx 4 inches), you are ready to make the crossover. Take the

right-hand piece and bring it up and over top of the left-hand piece,

towards the left, while simultaneously bringing the left-hand piece

under and to the right. Hold the pieces at about a 45 degree angle from

each other. Once you have crossed the right-hand piece over the

left-hand piece. Now for the tricky part ... you have to switch hands,

as right now your arms will be crossed; your right arm/hand will still

be holding the right-hand piece (now on the left side), and your left

arm/hand will still be holding the left-hand piece (now on the right

side). You have to bring the two ends down and switch hands, so that

your right hand will be holding what used to be the left-hand piece, and

vice versa.

Once you have accomplished this change of hands, pull the two ends

apart to about 45 degrees again. Now simply repeat the crossover step.

Continue to repeat this crossover process until you near the end of the

strips of bark.

I have found that some people have had one side tighter than the

other side, and when they have tried to bring the twisted piece over,

they will have only just "wrapped" this around the other piece. If you

do this, you will actually be placing the entire load on just one side

of the twisted bark.

You want to start off with equal tension on both sides, so once you

spread the twisted pieces across each other, you will be keeping the

tension equally on both sides. This will share the load, allowing for a

more equally strengthened binding.

It will seem awkward at first, as with any new skill, but practice is

always the key to proficiency. |

|

|

|

Photo 6

|

Photo 6 shows that after I have

completed this process, with the full length of my bark strip used

up, I now have a completed piece of very abrasive resistant and

string for of binding. To make a knot at the end of the strips of

bark, I have simply brought all the twisted strips together and tied

these through each other. Remember to keep it simple at first. You

can expand on your new skill later. This is the basic process of

fabricating some very strong, durable binding material. |

|

|

|

|

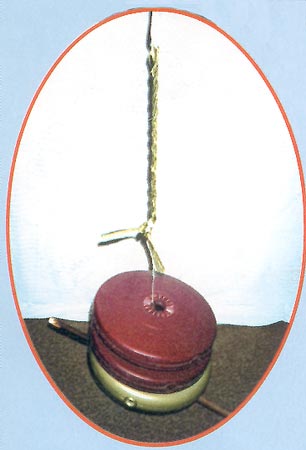

Photo 7

|

I tried an experiment with my new

binding. I used a small piece of binding that I had made and tied it

to three 25-pound weights. I hung these suspended above the floor,

as shown in Photo 7, and left it hanging for a considerable

length of time before removing it, to see how well it would hold up.

If a piece of binding can hold 75 pounds, it will be very practical

to use in the bush. |

|

|

|

|

I prefer to have different binding or cordage for different purposes; some

for quick and small tasks, and some for heavier loading. Take the time

to practice this skill. Experiment with other kinds of bark, and do not

always look for the perfect pieces as we have seen here. The strength of

the binding we just made was accomplished with a small sapling, and has

served our purpose.

From time to time in the bush, we use saplings for may different

things. Take the time to ask yourself: "Am I using it to the fullest

capacity?" In another article, about

snowshoes, I show how to

make improvised snowshoes. While reading this article, do you think of

using the bark first before making the snowshoes? If you do not, you now

have a new idea to think about -- the binding. It may be possible to

make binding from the bark of the saplings you use to make the

snowshoes. Then you will have a ready source of good binding with which

to ties the snowshoes together as you make them. Also, the binding can

be used to tie the snowshoes onto your feet.

When you first begin to work with this skill of making binding, think

of what else you could utilize this technique for. Think of all of the

situations you have been in and when this would have come in handy. You

might use it to tie the top of your shelter together, or during the

middle of the night you look out and see a foot of snow coming down.

Will you rest easy?

The next time you are making binding or cordage in the bush, ask

yourself a question, "Does this piece I have fabricated have the

capabilities to hold any substantial weight at all?"

There are many different materials around you in the bush to make

binding or cordage with. It is up to you to experiment and learn what

works best for you, and what materials are available in the area where

you are located.

I have made cordage and binding from many different types of

materials. I experiment with just about anything I can find in the bush.

I have even tried some man-made materials such as, gauze from a

first-aid kit, and the extra bottom piece that was on my long

shirt. Other materials have included dandelions, many different kinds of

grasses, cambium layers of trees, tree barks, and the list goes one. You

might not have willow bark where you venture out to, but think of the

concept, practice it, and then try materials you might have in the area

around you. Ask yourself, "Can I make a strong binding out of fresh cut

long grass?" Or, "What would happen if I took three of these twisted

bindings and braided them together?" Try any anything and everything. It

is for you to learn.

When you are in the bush, take the time to listen to Mother Nature.

She will show you that there are many options for you to use. Remember

that we are never really "stuck" in nature; we are just "stuck" without

options.

I will outline some more variations of binding making, and some other

applications to give you in Part II.

Go to Part II. |

|

|

Photographs and text on this page Copyright by Allan "Bow"

Beauchamp; used with permission of the author.

This article originally appeared in Wilderness Way magazine, Volume 6, issue

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|