|

|

Home →

Survival →

Cordage

Bows Bindings

- Part II

by Allan "Bow" Beauchamp

(go to Part I) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If you read Part I, you will see that

this article is just an extension of an already developed skill. |

|

|

|

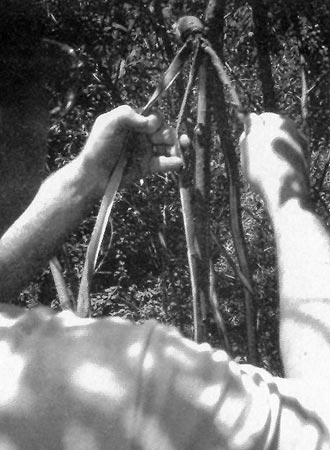

Photo 1

|

I have again acquired some more pieces

of sapling bark. Photo 1. This time, instead of taking one

piece of bark, and bending it in half over a stick, we will change

the way we will start to make our binding by attaching the tops of

the pieces together. This is done with a simple over-hand knot (it

does not have to be fancy; it just has to work.) |

|

|

|

|

Photo 2

|

This is your starting "bend." Choose

three individual pieces to work with. Photo 2. Start the

process, the same as before, by taking the right single piece and

twisting it to the right. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 3

|

Photo 3 shows utilizing the left

hand to assist in keeping the pieces separated, as well as holding

the tension on the other pieces until they can be twisted. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 4

|

Twist the first two pieces, continuing

all of the way down the pieces, before you twist the third piece.

Photo 4. This will make it easier to hold the first two pieces,

and twist the third piece. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 5

|

As you can see in Photo 5,

keeping these three pieces tensioned can be a task. This can be

accomplished simply by using your left hand to hold the third piece.

(Note: If you pre-twist the pieces, it will speed up the process.) |

|

|

|

|

Photo 6

|

Next, we will begin the crossover or

braiding. Photo 6. It will not matter if you start with the

right side or the left side, as long as you remember to keep the

tension in both sides equal (as described in the first article,

holding them approximately 45 degrees away from each other). I have

chosen to start by taking the left strip of bark, and bringing it

over the center strip. Then, 1 will take the right strip of bark and

bring it over the left strip of bark. |

|

|

|

|

This is not complicated if you have ever braided anything. Try following

this example, and then try some experimenting with each strand. Try it

several different ways. You will find that the process will take on its

own look. Try to get a feel for it, then make whatever changes that you

need. It does not really matter how it looks as long as it holds well,

and gives you the characteristics that you will need to use it for.

Remember to keep the tension equal. This will allow equal sharing of the

load on all sides of the cordage. |

|

|

|

Photo 7

|

Make the length of the binding whatever

size you will need it to be. Then, simply tie one strip of bark to

the other. Photo 7. |

|

|

|

|

Photo 8

|

Snug up the knot, and tie up the other

two pieces using the same method. Photo 8. You do not have to

be too concerned with using the right knots. If it holds the end

tight, it will work fine. If you wish to trim the ends of the strips

of bark away at this point, keep in mind, that if a load is applied

to the binding, there will be some stretching. Always leave extra

bark at the bottom for movement. |

|

|

|

|

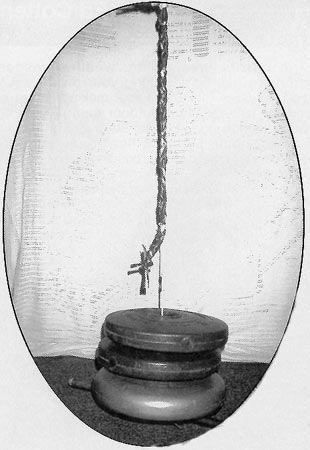

Photo 9

|

Next, you can test the binding using the

same experiment that was used in

Part I. Tie the binding to three 25-pound weights suspended

above the floor or ground. Photo 9. Leave it hanging for a

considerable amount of time before removing it to see how well it

will hold up. If a piece of binding can hold 75 pounds, it will be

very practical to use. |

|

|

|

|

Think of the many ways you can expand on this idea, and apply it using

your new skill. Instead of using three single pieces, take six double

pieces, and braid them together. How much will they hold? As you can now

see, there is no end to new ideas to this technique. |

|

|

|

Photo 10

|

Another example is shown in Photo 10.

The string was taken off of a bow, and the same willow bark binding

technique was used. It makes a fine bowstring, with good abrasion

resistance properties. |

|

|

|

|

Go to

Part I |

|

|

Photographs and text on this page Copyright by Allan "Bow"

Beauchamp; used with permission of the author.

This article originally appeared in Wilderness Way magazine, Volume 6, issue

1 |

|

|

|

|