|

Any archery fan can add more enjoyment to the sport by

home-crafting primitive equipment. I'm an ardent primitive hunter. That is, I pursue game as the American Indians

did: I pick up an animal's trail, identifying species, size, and (sometimes) sex

… stalk the prey to within pulse-quickening distance … and bring it down with a

well placed arrow.

Now bow-hunting is a challenge in itself, but the

experience can be further enhanced by making your bow and arrows, using -- as

far as possible -- the same materials, tools, and techniques that have been

employed by bowyers for millennia. Of course, any number of excellent bows are

available on the market today, but it's my opinion that no factory-made item can

match the look and feel of a handcrafted bow.

I've fashioned many different types of bows, each designed to fit a special

hunting need: short, highly reflexed, sinew-backed weapons like those developed

by the American Plains Indians … long, recurved wooden bows in the style of

those used by Eastern Woodlands Indians … English longbows … and models that

borrow features from several other types.

As a professional tracker, stalker, and close-range hunter (I teach these

skills for a living),

I prefer a bow that's recurved like an Eastern Woodlands model but shorter, with

sinew backing -- for strength and longevity -- and a twisted-sinew bowstring.

Shorter bows are easier to handle when I'm stalking through heavy brush and

making close shots with a minimum of elbowroom. For rainy day hunting, however,

I’m frequently forced to use a longer recurved bow that’s fitted with a

plant-fiber bowstring, which resists moisture-induced stretching. For bow

fishing, on the other hand, I prefer a longish self – or straight – bow.

Of course, most folks can’t afford the luxury of owning three different bows

… unless they make the weapons. So I’m going to tell you how to construct your

own archery tackle, using (for the most part) the techniques of the American

Indians … with frequent hints on how to speed up the process when you’re in a

hurry. Keep in mind that we’re not going to be covering the making and use of

survival bows, which are a different breed. Those weapons can be cobbled

together quickly and easily from whatever materials may come to hand, and

they’re suited only to very close-range shooting. Rather, this discussion will

concern the crafting of precision weapons: high-quality bows that will reward

your patience and effort with years of reliable accuracy.

Some of the techniques may sound a bit difficult, but don’t let the fear of

making an error keep you from trying your hand at them. The raw materials needed

are inexpensive or free, and experience is a great teacher … so read on, jump

right in, and make a few beginner’s mistakes, if need be. Keep at it, and you’ll

become proficient in the bowyer’s ancient art. I’m certain you’ll be glad you

did.

THE BOWYER'S BARE ESSENTIALS

To craft bows of high quality, all you need is a small workspace, a few common

hand tools, four inexpensive C-clamps, and a woodstove or other source of heat.

Nature will provide the rest of your tools and – if you keep your weapon

strictly primitive – all of your materials.

In some parts of the country, the traditional woods for bowmaking are

hickory, honey locust, mountain mahogany, and juniper. The best bow woods are

Osage orange (bois d’arc), yew, and ash. For the long recurved bow and the

longbow, I prefer white ash, which makes a good beginner’s wood for any style of

bow because of its “forgiving” qualities. Generally, though, Native Americans

used whatever materials were readily available, and you can do the same. If none

of the wood varieties I’ve mentioned grow in your area, you can even order a

straight-grained plank of appropriate size through a specialty hardwood dealer

(but be certain that the wood hasn’t been kiln dried).

If you want to harvest your own wood, look for a small tree that’s about 2”

to 3” in diameter, free of knots and blemishes, and straight. About 5½

feet should be a good length for any design except the longbow, which will need

about a foot more. You can also use a smaller sapling for a bow stave: Search

out one that's a little more than an inch through through the center and meets

the aforementioned requirements. The best time to cut wood is in February, when

the sap is down. Remember that the wood is a gift from the Creator and should be

taken with respect.

I season my staves by storing them in the shed until spring, then bring them

indoors until the wood has aged for a full year. The wood needs to be kept in a

cool, dry place during the seasoning process to prevent warping. If the thought

of having to wait a year before starting to work on a bow stretches your

patience, just buy an air-dried stave from your hardwood dealer and get right

down to business.

Once the wood has seasoned, it's time to remove the bark. Instead of carving

away the skin, scrape it off by holding a sharp knife at a 90 degree angle to

the wood ... so the blade won't slip and nick the stave. If you use a sapling,

carefully split the skinned pole down its full length. If you're cautious, you

can sometimes split two usable bow staves from a single sapling, but I don't

trust my splitting all that much and would rather carve with a drawknife until

the desired thickness is reached. Bows made from sapling will have a

semi-circular cross-section.

|

If you're

careful, you can split two usable bow staves

from a single sapling of about 1" diameter.

In the right hands, a larger sapling or limb

can be split into four staves. All

subsequent shaping must be done with

abraders; whittling can weaken the wood and

may cause nicks. |

|

| |

|

Use a rasp to

work the handle down to a size and shape

that feel comfortable in your hand. Thin and

taper the limbs gradually toward the bow

tips. There is no one best size or shape for

a traditional American Indian bow, but

strength and aesthetics should be taken into

account. |

|

|

If you use a larger tree for a stave, split it carefully in half, then --

perhaps -- in half again. (Some of the instructors at my wilderness skills

school can get four usable staves from a 3" diameter tree!) Bows made from a

small tree will usually have a slightly curved, rectangular cross section.

After you've made your initial splits or have shaped the stave with a

drawknife, all subsequent scraping will have to be done with scrapers, abraders

(rasps or files), and sanders ... since too much whittling will "thin out" and

weaken the wood's grain.

|

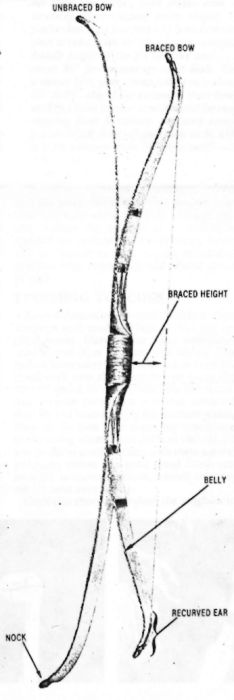

The Language of

Archery |

|

Like many specialized fields of human interest,

archery and bowmaking have their own jargon ... but by

reviewing the terms below you'll soon be able to "talk

archery" with the best of them!

- Back: The side of a bow that faces

forward, or away from the archer.

- Belly: The inside of a bow ... the side

facing the archer.

- Brace: To string a bow.

- Braced Height: The distance between the

string and handle of a braced, or strung, bow.

- Bowyer: The little old bowmaker.

- Draw: The distance, measured in inches,

that an archer pulls the bowstring.

- Ears: The forward-curving tips of a

recurved bow.

- Fletching: Feathers that have been split

in half and attached to the back portion of an arrow

to give it stability in flight.

- Limbs: The body of the bow exclusive of

the handle.

- Longbow: A straight wooden bow

approximately 6 feet long, with no reflex of recurve,

popularized in England during the Middle Ages..

- Nock: The notch in the back of an arrow

that receives the bowstring. Also, the notches on a

bow's tips that hold the bowstring in place. As a

verb, nock means placing an arrow on the

string.

- Recurved bow (or "recurve"): A bow having

the ends of its limbs bent forward.

- Reflex: A bend at the midpoint, or

handle, of a bow that causes the limbs to bow

slightly forward when unstrung.

- Self bow: A plain wooden bow, with no

reflex, recurve, or sinew backing. A longbow is a

self bow.

- Shaft: The body of an arrow, minus

fletching and point.

- Stave: A piece of wood from which a bow

is made.

- Weight: The strength, measured in pounds,

required to pull a bow to full draw. (Full draw is

generally considered to be 28".)

|

|

BENDING TO THE BOWMAKING TASK

With the stave aged, peeled, split, and rough shaped, you're ready to get on

with the real work of making a bow. At this point, it's a good idea to "ask" the

wood what type of bow it wants to become rather than trying to make it what you

think it should be. In other words, take into account the wood's quality, grain,

and growth patterns in deciding how to shape the tool that it will become.

Generally speaking, wide and thin is the best shape for softwood bows. The

extra width is necessary to help prevent cracking. Softwoods tend to splinter

more readily than do the less brittle hardwoods, so hardwood bows can be made a

little thicker and quite so wide.

When I produce my bows, I never rely on tape measures or calipers. I've

learned to rely on what feels good for me and for the wood. Thus, the dimensions

given in this article are by no means law ... they're only averages to help you

in making your first bow. After you've shaped one or two, you'll be able to use

touch, sight, and your own inner feelings to make a bow that's as personal as

your fingerprints.

This initial steps in making a bow are the same, no matter what design you've

chosen for the finished product. First, cut the stave to the length you want

your bow to be when completed (here, I'll be discussing one that's 5 feet long).

Now, find the longitudinal center point and measure out about 3" in both

directions (this 6" area will become the grip, or handle). The next job is to

taper and thin the limbs. Starting from the outside of the grip area, and using

a rasp or coarse-toothed file, begin thinning and tapering ... from a thickness

of about 5/8" at the handle, down to 3/8" at the tips (you want to achieve a

smooth, even taper). The width should slope from 2½" or so

near the handle to about ½" at the tips. As you work on this phase of the

project, be sure to keep the back and sides of the bow as flat (as opposed to

rounded-off) as possible ... and also take care not to overdo the thinning.

Now, work on sculpting the handle to a size and shape

that pleases your grip. Thin the handle area in width and thickness until it

fits your hand comfortably, and the put the finishing touches on the overall

shaping of your bow with a finer file, such as a mill file. And, while you have

that mill file in hand, go ahead and cut string notches in the end of each limb

... deep enough to hold the bowstring in place but not deep enough to weaken the

bow limb tips.

With that done, it's time to test the bow to see if the

limbs pull evenly. Tie a strong cord from tip to tip -- as if it were a

bowstring -- then place your bare foot on the handle and pull upwards on the

center of the cord until the limbs begin to bend. Be careful not to pull the

ends up very far at this stage, since excessive flexing might cause splitting if

the limbs aren't even. If you find that one limb pulls easier than the other,

carefully abrade away the belly of the stronger side, using a mill file, until

the limbs pull evenly. (The evening process is known to bowyers as "tillering".)

While performing this test, you'll also get some idea of the draw weight your

bow will have when finished. Though you can increase the stiffness of a

too-flexible weapon by applying sinew backing, being able to predict its draw

weight in advance requires long experience and liberal doses of luck.

FINISHING TOUCHES

Native American bowyers finished their weapons with

rendered bear or deer fat, applied warm. Deer brains were sometimes used instead

of, or together with, the fat. The Indian bowmaker would then set or hang his

handiwork near the lodge fire to warm the fat and speed its absorption into the

wood. My personal preference is to mix rendered deer fat and brains, apply the

mixture warm, then set the bow high above my woodstove so the rising warmth can

drive in the oils. (If you prefer to avoid working with these natural products,

almost any good wood finish can be used, including varnish, linseed or cedar oil

... and even lard.)

Once this chore is finished, the longbow is ready to

shoot. Go easy at first, giving your new hunting tool a chance to break in.

Sometimes, though, no matter what you do in an effort to prevent it, a new bow

will snap. This is probably due to a flaw in the wood rather than something you

did wrong, but in either case there's nothing to do except try again, using your

newly gained experience to ease and improve the next effort.

We'll discuss the details of sinew backing a little

later on, but it should be briefly mentioned at this point that sinew will keep

a new bow from breaking, improve its snap and cast, and add pulling pounds to

the limbs. I therefore suggest that all your bows be sinew-backed, even though

the technique was not traditionally used on longbows.

PUTTING THE CURVE IN A RECURVED BOW

To enhance your hunting weapon's speed, power, and beauty, you may want to

add recurve to the limbs. For a recurved bow, follow the instructions for the

self bow and longbow but stop short of applying the brains and fat. What you're

going to do now is to bend the last 6" or so of the limbs forward. Set a

large pot of water (a big coffeepot is perfect) on the stove to boil. When it's

bubbling, dip one end of the bow into the water, up to about 9", and let it

"cook" for 3½-4 hours. While the bow end is in its hot

bath, cut a recurve form -- as shown in an accompanying photo -- from a piece of

scrap 2x4 lumber (you'll need one for each limb). The exact curve of the form is

up to you, as long as it is not beyond the bending capabilities of your stave.

|

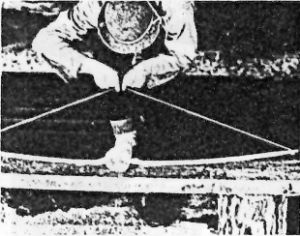

With the basic

shaping of the bow completed, it's time to

check the evenness of limb-pull. Tie a stout

cord from end to end of the bow, place your

bare feet on the handle, and pull up gently.

If one limb is stronger than the other,

carefully abrade away belly wood until the

limbs pull evenly. |

|

| |

|

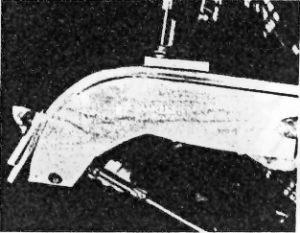

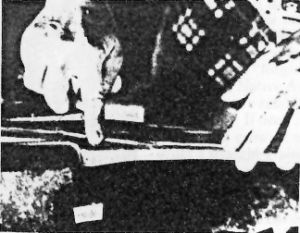

To put the

curve in a recurved bow ... boil the bow tip

for 4 hours, then place it over the convex

side of a 2x4 form. Lock the tip in place

witha C-clamp, then bend the limb

around the form and lock it down with a

second clamp. Allow at least 24 hours before

removing the clamps. |

|

|

When the first bow-end has finished boiling, place it over

the convex side of the form and secure it with two C-clamps. The best approach

here is to fasten the tip of the limb in place first, then -- using the bow as a

lever -- slowly bend the limb back over the form and clamp it down securely. (To

keep the limbs from getting dented, use small blocks of soft wood between the

clamps and the bow.) At this point -- with the first end of the bow locked over

the bending form -- start cooking the other tip ... then repeat the clamping

process. Now, give the bow a full day of rest in a warm, dry place.

The next step is to remove the clamps and fine-tune your

newly recurved bow. Tuning is accomplished by removing a little of the belly

wood at the point just before the recurve begins. I usually take off 1/16" to

1/8" of belly wood, starting at the base of the recurve and working back about

6" toward the handle. I find that after I've done this fine-tuning, the bow has

a faster action and reduced kick, or jolt. (Some bowyers say that this final

shaving keeps the recurve's "ears" from snapping off, too.) Once your bow is

tuned, you can either sinew-back it or finish it up as you would a longbow.

And if you want to give your hunting tool even more zip and

zing, you can add a reflex to the bow by bending the back slightly forward. Just

heat the handle area over a steaming kettle of water for a couple of hours, then

lay the bow -- its back facing down -- over a small log, and stand barefooted on

the limbs until the wood has cooled (it doesn't take all that long). This will

produce a forward curve or reflex, adding even more punch to the weapon. (Reflexing

is especially important for extremely short bows similar to the stubby "horse

bows" that the Plains Indians used so effectively against the tough-hided

buffalo.)

|

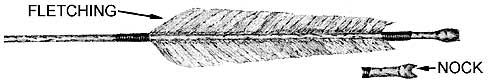

Arrowmaking:

Straight and Fast |

| |

|

|

| |

| To complete your primitive-archery out-fit, you'll

want a supply of arrows to go with your custom-made bow

... projectiles that are every bit as functional and

beautiful as their launcher. Cherry, serviceberry (Juneberry),

ash dogwood, cedar, bush blueberry, and even cane and

reed are good woods to use for arrow shafts. Cut

sections about 3 feet long from saplings with base

diameters of ½" or so, and

take the time to search out knot-free shafts. Collect

your arrow wood during the winter, when the sap is down.

After bundling the shafts together into tight packages

tied every few inches with cord, let them season as you

did your bow stave. When the shafts have aged for a

full year, remove the bark, again by scraping

instead of carving (because they are so much thinner

than bow staves, even greater care is necessary when

shaping arrow shafts). If you're shooting a 5-foot-long

bow, measure your arrows from the tip of your extended

middle finger to the pit of your arm ... about 30" for

the average adult male. For a shorter bow, your arrows

will be only about 23" - 25" long. (The extremely short

bows used by Plains Indians were designed for easy

shooting from horseback and were rarely pulled to full

draw. If you want to be able to shoot a long arrow at

full draw, you'll need a bow that's at least 48"

long, preferably longer. Otherwise -- even if the bow is

well-made and doesn't break -- your fingers will suffer

string pinch due to the acute angle formed when a short

bow is overdrawn.)

Using coarse-grained sandpaper, smooth the arrow

shafts down to a diameter of about 5/16". Then switch to

a fine-grit paper or emery cloth for finishing. Once the

shafts are smooth, rub them with rendered fat and warm

them near the fire to induce absorption of the oils. (Of

course, you could also simply buy 5/16" hardwood

dowels.)

Crooked arrows can be straightened by heating them,

bending the kinks out with your fingers or your teeth,

and holding the shafts straight until they cool.

Sometimes it's necessary to use an arrow straightener,

or wrench, to unbend stubborn spots on an arrow. To make

this tool, drill a shaft-sized hole through a piece of

antler or bone. Then stick a heated shaft through the

hole and use the wrench as a lever to bend out the

kinks. |

|

|

| Next comes the fletching. I find that a 6" long

fletching, trimmed to a height of about

½", provides good aerodynamics and

closely resembles the traditional Indian style. Turkey

tails feathers are the best, but the tail plumage of

almost any large of medium sized bird will do in a

pinch. (Just be sure not to use feathers from any of the

many protected species of birds or you'll be

letting yourself in for a federal-type felony!)

You'll need three fletches for each arrow. Start by

cutting longitudinally along the median line of each

feather's quill, splitting the feather into two equal

halves. After carving away the pith and excess quill,

trim the feathers to the proper height, and check to see

that they're all of a uniform size and shape.

To fasten the fletches to the arrow's shaft, hold the

backs of the feathers in place at the nock end of the

shaft, and bind the fronts of the feathers to the arrow

with a wrapping of moist sinew. (Some bowyers

temporarily anchor the fletches to the shaft with pine

pitch or diluted hide glue, thereby feeing both hands

for the wrapping chores.) Apply the sinew by first

separating it into threads, just as you did for the bow

backing, then wetting it with saliva and wrapping it on

evenly. The saliva-and-sinew mixture forms its own glue

and doesn't have to be tied. After the front wrappings

have dried, repeat the process at the back of the

fletchings, wrapping up to the base of the nock. The

dried sinew is almost transparent, lies close to the

shaft, and tightens up even more as it ages.

To cut the bowstring notches in the backs of the

arrows, abrade a U-shaped slot with a small rat-tail

file (or saw carefully with a hacksaw) down to just

above the top sinew wrap behind the fletching. The nock

will then be supported by thee sinew wrap, preventing

the shock from the bowstring from splitting the shaft.

Be sure to position your string notches so that when the

arrow is shot, two feathers will pass across the bow

evenly, with the third-or "cock "-fletching protruding

at a 90º angle away from the

bow.

The size of the arrowheads and the notches that will

hold the heads onto the fronts of the shafts will be

determined by the animals you plan to hunt, your

personal preference, and your state's laws. In my state,

as in most, it's illegal to hunt big game with anything

other than a wide steel broadhead. Steel heads can be

cut from any source of thin sheet steel, using a jigsaw

or tin snips, then filed and honed razor-sharp. (The

Plains Indians actually got much of their arrowhead

metal from the iron rims of wagon wheels.) Take care to

make the proper base shape -- or notch -- on the backs

of the heads so they'll fit snugly into the arrow-shaft

notches and provide a good anchor for sinew wrapping.

Bone arrowheads can be almost as sharp and deadly as

steel broadheads. Just use the cannon bone from the

lower of a deer; split the bone in half, file to shape,

and sharpen.

Then too, stone points can be chipped from flint,

chert, jasper, quartz, obsidian, and even glass.

Flint-knapping is a complex topic and would require an

article of its own for even a cursory treatment, but

tests have shown that well-made stone heads can achieve

even greater penetration than steel.

OK ... you've formed your arrowheads -- steel, stone,

or bone -- and cut the slots they'll fit into on the

arrow shafts. Now it's lime to bind the points to the

shafts: Just slip the heads down into their notches and

apply a good wrapping of spittle-moistened sinew, as you

did with the fletchings.

Once the heads have dried in place, your arrows are

ready to shoot.

For hunting, it's best to leave the shafts more or

less natural or to crest them with subdued colors. But

for target practice, you might apply decorative stripes

to your arrows ... an artistic touch that will also help

you follow those erratic shots that will inevitably send

an arrow slithering beneath a cover of grass and leaves. |

| |

|

|

|

SINEW-BACKING BASICS

The two ingredients necessary to sinew-back a bow are sinew

from the leg and back tendons of animals, and hide glue (made from. hide

shavings and hooves). I prefer to use the leg

sinew of deer and elk ... though horse, buffalo, cow, goat, and moose sinew work

just as well. If you're not a hunter -- and don't know one -- arrange to buy

tendons from the local slaughterhouse. Usually, the people there will just give

them to you (and probably decide that you're a bit strange).

After cutting the tendons from the legs and back of an

animal, prepare the sinew by removing the clear sheath that holds the tendons

together. Then place the exposed bundles well above a heat source to dry. When

they're no longer moist, pound the tendons on a board, using a wooden mallet or

a smooth rock as a hammer to separate the bundles of tissue into individual

threads. To prepare hide glue, put hooves, hide

scrapings, and dewclaws into a pot with just enough water to cover them, and

boil the "stew" for several hours. (To get a finer consistency, you may want to

skim off the scum that bubbles up to the top of the boiling pot.) You'll end up

with a thick, glompy mass of glue that's perfect for the job of welding sinew

strips to wood. (An alternative to homebrewing is commercial hide glue,

available at many hobby shops in both liquid and powder form. But the

store-bought stuff lacks the authenticity -- and rousing aroma -- of the

homemade material. You can forget about epoxy and other chemical binders: They

definitely won't work.) When you get ready to use

the glue, keep the container warmed in a water bath atop the stove (120°F or

thereabouts is perfect), since at room temperature the adhesive gets gummy and

sets up too fast, especially if your workroom is cool to begin with.

Prepare your bow to receive the glue and sinew by roughing

up the back with a hard, abrasive rock. Make sure the wood is cleaned of any

greasy fingermarks or dirt, then paint the bow's back with hide glue that's been

thinned in a ratio of about two parts glue to one part warm (preferably

distilled) water. Next, wet the sinew strips and place them -- a few strands at

a time -- into the hide glue to soak for a few minutes.

Squeegee off excess glue as you remove each piece of sinew

from the glue pot, and -- starting at the longitudinal center of the bow and

working out toward the tips (or the other way around, if you prefer) -- apply

strips of glue-soaked sinew, laying them parallel to the limbs and as straight

as possible. Cover the entire back of the bow with the sinew, and try to make a

smooth job of it, staggering the ends of the strands to avoid making seams.

Apply sinew all the way to the tips of the limbs, then fold about 2" over to the

belly side to strengthen the tips. Once the back is sinew-covered, let it dry

awhile, then apply two or three more coats of sinew and glue. When you're

finished, let the bow rest for at least a couple of weeks.

After the sinew has cured, shoot your weapon a few times at

half draw to see if it needs any more fine-tuning. If you find that you need to

even up the pull of the limbs again, simply tiller the sinew just as you did

with the belly wood earlier. (Sinew works well under a mill file.) Finally,

finish your bow with a mush of rendered fat and deer brains, as described for

the longbow. This time, however, don't place the bow near heat.

As time goes by, you'll find that the sinew continues to

pull against the bow's belly, producing a forward curving, or reflex ... but

don't be alarmed, since more reflex will only strengthen the weapon. After a

year or two, the sinew will have pulled all it's going to, and your bow will

have assumed its permanent shape and shooting characteristics ... and will last

a lot of years if properly cared for.

|

The two

ingredients necessary to sinew-back a bow

are sinew fibers from the leg or back

tendons of animals, and hide glue (which can

be prepared from raw materials or

purchased). After the tendon bundles are

dried and pounded, they will separate into

individual strands. |

|

| |

|

To apply

sinew, first rough up the back of the bow to

provide a good gripping surface for the

glue. Wet the sinew strands, soak them in

hide glue, then apply them in parallel rows

until the entire back of the bow is covered.

Allow the glue to dry, and then apply two

more layers. |

|

|

STRING THAT

BOW Reverse-wrapped sinew is the traditional

fair-weather bowstring. And for wet-weather shooting, the fibers of plants such

as velvetleaf, hemp, dogbane, and nettle work admirably. By reverse-wrapping a

string to more than twice the length of the bow, then folding the cordage in

half and reverse-wrapping it again, you'll produce a strong and durable

bowstring with a loop at one end. The other tip end can simply be tied to the

bottom limb. (For a photo-illustrated guide to reverse-wrapping, see my article

"Making Natural Cordage" in MOTHER NO.79, page

38.) And, of course, those of you who are in a hurry can just trot down to the

local sporting goods dealer and purchase a ready-made bowstring of the

appropriate length. To determine the correct

bracing height for your bow (and -- in turn -- the correct length for your

string), place one fist on the inside of the grip and extend your thumb as if

you were trying to flag a ride ... the attached string should just touch the tip

of your outstretched digit. PARTING SHOTS

Before Europeans entered the picture with their advanced

technology and metal tools, Native American bowyers painstakingly fashioned

finely crafted bows with stone and bone implements. The process took a lot

longer, but Stone Age humans weren't as frantic about the passage of an hour as

today's ulcer-ridden people tend to be. And those earlier products were often

every bit as beautiful and serviceable as fine machine-laminated bows.

Archery has had a long history not only in the Americas but

in virtually every corner of the globe except Australia. The ancient Turkish

horn-and-sinew composite bows -- to cite one shining example -- were quite

probably the most effective primitive weapons the world has ever known. Bows are

silent, pinpoint-accurate in practiced hands, designed to test the hunter to the

extremes of his or her skill ... and they offer the game animal a sporting

chance. [EDITOR'S NOTE: As you know, there's a

great responsibility placed upon the hunter who uses primitive weapons ... to

develop his or her accuracy to the maximum and to avoid taking any shots that

might result in losing a wounded animal.] In

addition to saving the hundreds of dollars that it would cost to equip yourself

with a top-quality modern compound bow and fiberglass or aluminum arrows,

hunting with a piece of wood that's taken on a beautiful shape under your own

hands can help you achieve harmony with nature and the past, a harmony which has

all but disappeared from our over-mechanized, depersonalized world.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: Native American Archery by Reginald

and Gladys Laubin is the ultimate authority on this subject and can be ordered

from The University of Oklahoma Press. Clothbound and in large format, the book

goes for $18.95 plus shipping and handling. It's a steep price, but for the

serious archer, bowyer, or historian the book is worth every penny.

For more material by and about Tom Brown Jr. and the Tracker School

visit the Tracker Trail

website.

|